On 10th November I met some colleagues from the History of Place research project to attend a talk by Roddy Slorach called A very capitalist condition: a history and politics of disability. We met in Starbucks in plenty of time to enjoy a gingerbread hot chocolate and discuss what we were hoping to learn in the lecture.

The speaker Roddy, who was interpreted by a BSL interpreter, began by asserting that contrary to myth, disability is a form of discrimination, and is a recent concept, not present throughout most of history. Defining disability itself can be a difficult matter. Roddy asked, why, for example, did his need for glasses not count as a disability, when his hearing impairment does?

Recent uses of DNA testing and other archaeological practices have shown the presence of disabled people even in hunter-gatherer societies, when people could only have survived if they had others to help them.

Roddy gave a brief summary of the history of disability. A Chinese engraving from around 525 A.D. is one of the earliest depictions of a wheeled chair and recent uses of DNA testing and other archaeological practices have shown the presence of disabled people even in hunter-gatherer societies, when people could only have survived if they had others to help them. Roddy argued the turning point in our approach to disability came with urbanisation and industrialisation, when people had less control and began to have their lives dictated to – this coincides with the rise of workhouses and asylums. Roddy however argues that it wasn’t just the changes of industrialisation but a more fundamental reason for the creation of disability – capitalism. Capitalists see disabled people as harder to exploit – there are often extra costs to employ a disabled person. The need to profit, Roddy argues, created disability.

Roddy argued the turning point in our approach to disability came with urbanisation and industrialisation, when people had less control and began to have their lives dictated to – this coincides with the rise of workhouses and asylums.

A short break was taken to rest voice and hands, and the second half of the lecture began with a short history of the rise of eugenics in the 20th century. I was most surprised to learn that the first International Eugenics Congress was held in London in 1912. Incidentally, ‘normal’ only appears in the English language in the 1830’s, coinciding with the rise of colonialism and the increasing categorisation of people, just a short step to hierarchical thinking.

Though he recognises them as important, Roddy pointed out that the Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990) and the Equality Act (2010) are based on the idea of ‘reasonableness’. They are founded on the issues of resources and costs, undermining individuality. The talk highlighted that equality isn’t about treating everyone the same but about embracing individualities.

After the talk there was a chance for questions, followed by wine and discussion in the foyer, which gave me a chance to express my interest in archaeology and the huge amount of research there is to do on the topic of disability archaeology. Roddy Slorach said he was keen to keep in touch with me and the History of Place team to discuss discoveries made during the project. I am looking forward to reading his book and learning more.

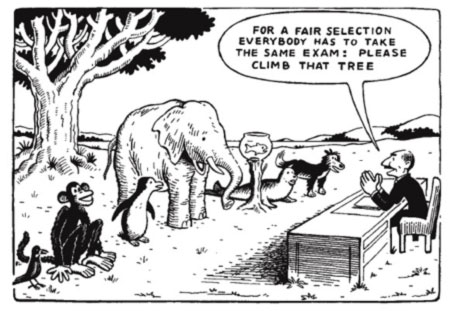

This cartoon shows a bird, monkey, penguin, elephant, fish (in a bowl), seal and a dog with a man telling them “For a fair selection, everybody has to take the same exam: Please climb that tree”.

It is a copy of a cartoon by Hans Traxler from 1976 and is usually accompanied by a quote incorrectly attributed to Einstein – “Everyone is a genius but if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree it will spend its whole life believing it is stupid.”