For most dispossessed people in late Medieval and early Modern England life was, in the words of Thomas Hobbes, “nasty, brutish and short.” For the lucky few however help was at hand in the form of hospitals.

It is important to understand that these were not hospitals in the sense that we would understand today. Instead you could compare them to a mixture of modern day hospices or care homes, and the type of charitable almshouses that still exist to meet the wants of the needy within the community.

Those found guilty by the testimony of their peers of being “a common drunkard, a quarreller, a brawler, a scold, or a blasphemous swearer” could expect to spend some time in the stocks on a diet of bread and water.

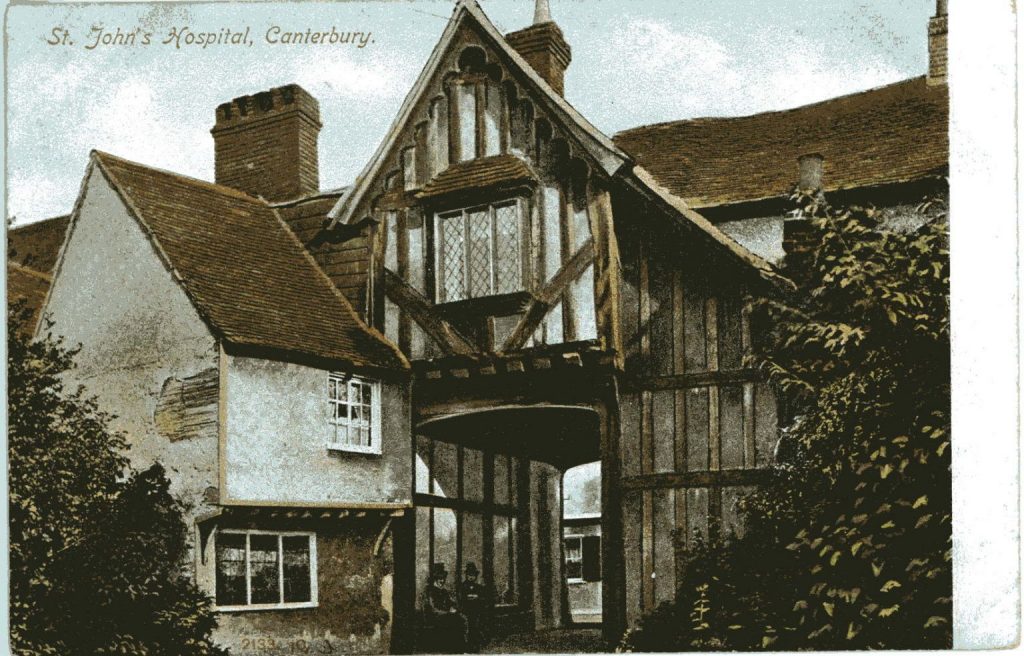

One of these, the Maison Dieu in Faversham, Kent, has already been discussed within other blogs in the History of Place project. This blog deals with the written ‘Statutes’ and ‘Regulations’ providing for two more, the hospitals of St John’s, Northgate, and St Nicholas, Harbledown, both within the auspices of the See of Canterbury. These give a valuable insight into the lives of the inmates of these institutions, and the duties expected of those charged with the upkeep of their well-being.

The first thing to note is that space in these hospitals was limited, and potential inmates had to meet a number of strict criteria. In his ‘Statutes’ of September the 15th, 1560, Matthew Parker, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sets aside sixty spaces divided equally between men and women in St John’s, Northgate “for poor, sick, needy and impotent people to be relieved and succoured in the same.”

Naturally for the times only Protestants need apply, those who could “say the Lord’s Prayer, the Articles of the Faith, and the Ten Commandments…in the English tongue,” rather than, it should be noted, Latin.

But not anyone could become a ‘Brother’ or ‘Sister’ in this establishment. Naturally for the times only Protestants need apply, those who could “say the Lord’s Prayer, the Articles of the Faith, and the Ten Commandments…in the English tongue,” rather than, it should be noted, Latin.

Moreover, these ‘poor’ and ‘needy’ folk would still have to stump up six shillings and eight pence upon entering into the fold “towards the maintaining and repairing of the church and the other houses.” This would suggest that those who were offered places came from the ranks of what would later be known as the ‘genteel poor’, those who had fallen on hard times and whose families could not support them in the long term, but were able to contribute to their initial care. Once ensconced, the inmates might expect to receive this same sum on a quarterly basis to cover their upkeep, though eight pence would be withheld to pay the stipend of a priest to take care of their spiritual well-being.

No drinking, brawling or swearing

Archbishop Parker also outlined ways in which the moral probity of the hospital inmates was to be maintained. Those found guilty by the testimony of their peers of being “a common drunkard, a quarreller, a brawler, a scold, or a blasphemous swearer” could expect to spend some time in the stocks on a diet of bread and water. This same punishment was also meted out to those talking, sleeping or making unseemly noise at times of prayer. This seems inappropriate to the modern eye, but highlights the belief within the Church that spiritual wrongdoing, as they saw it, imperilled the soul and therefore must be strongly curtailed. However, those guilty of more corporeal crimes might expect longer periods in the stocks than their dozy or noisome partners in crime, which at least shows the Medieval Church making some concessions to mercy. Those who committed an offence for a fourth time though would find that quality stretched to breaking point, and persistent recidivists would have their place in the hospital withdrawn. ‘Adulterers and fornicators’ on the other hand would be given no leeway and were expelled immediately if found guilty by their peers.

Collecting the rents

Those accepted as ‘Brothers’ or ‘Sisters’, as the inmates were known, were expected to live within the confines of the hospital precinct, unless they were given express permission to remain outside. The hospital was administered by a Prior, chosen yearly by the ‘Brethren’, who would nominate four able bodied men among the inmates to serve as his “assistants and counsels”. Likewise, the ‘Sisters’ chose a Prioress to tend to their needs.

Twice a year at least, the Prior and his assistants would tour the hospital ensuring that the buildings and surrounding lands were in good order, and collecting “rents and sums of money due to the house.” This would then be placed in a large chest with three keys, one of which would be held by the Prior, the remaining to be held by two of his trustees. Thus we find that some of the inmates were empowered to reach a position in society that would have been denied them had they not been accepted into the hospital.

Light fingered administrators?

Just over a century later these once clearly defined, financially well-regulated institutions seem to have degenerated to the point that Archbishop Sancroft felt the need to try and regain a semblance of order. His ‘Regulations’ of 1686 are an attempt to stem abuses that were draining the resources of the hospitals. People could be fined for living outside of the precincts without the consent of the hospital authorities, other parishes who tried to offload their own needy souls would have to provide financial security up front, and inmates would not be allowed to move other family members into their rooms except for those needed as personal carers.

Luckily for the Archbishop, he could sometimes rely on the generosity of others to help support the work of the hospitals. In 1694, as witnessed by an ornate marble tablet adorning the wall of St Peter in Thanet Church, Broadstairs, Elizabeth Lovejoy left ten pounds to St John’s Hospital, and another five pounds each to two more hospitals in Canterbury.

Brutal as these rules and regulations appear by modern standards, these hospitals offered a select few a route out of abject poverty.

This is an extremely good suggestions particularly to

those new to blogosphere, brief and precise info… Thanks for sharing this one.

A must read article.