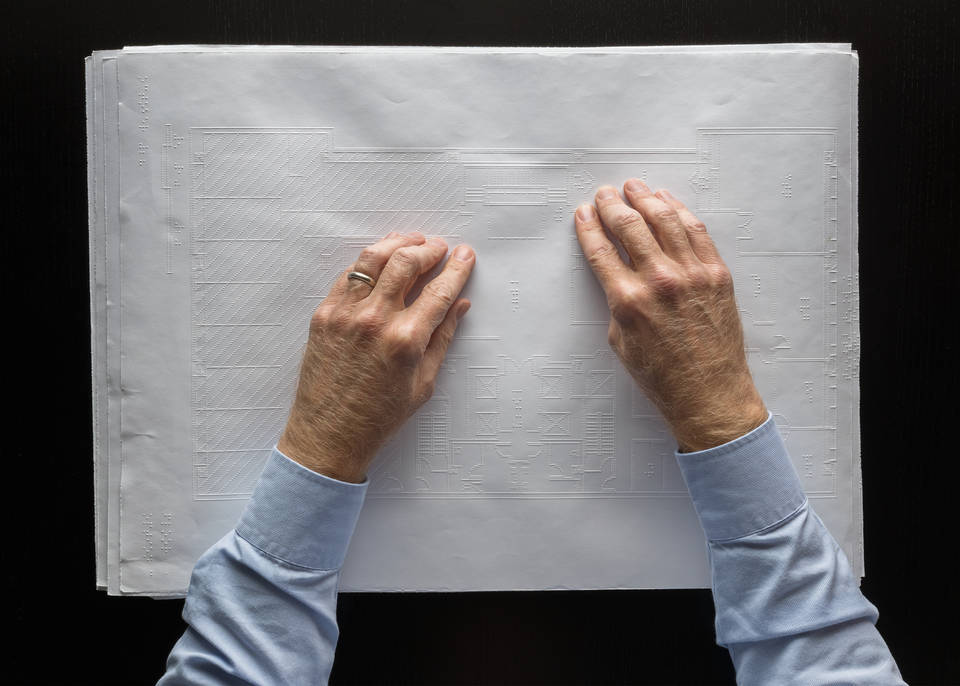

Our third museum display, created in partnership with the V&A. will remain on show until 20th October 2018. Without Walls: Disability and Innovation in Building Design looks at how disabled people have become a force in creating innovative design with striking accessible features. As well as featuring the eight places investigated by the History of Place project, it also looks at modern designs, a number of which were created by disabled architects, and how architectural plans can themselves be adapted, so that disabled people can design or comment on the design of new buildings.

There’s also a look at innovative collective housing, from Maggie and Ken Davis’ home at Grove Road built at Sutton-in-Ashfield in 1976, to Hogeweyk Dementia Village, designed to help residents live as independently as possible.

The house with the moving room (plus a giant silver cushion)

Maison à Bordeaux is a private home built into a hillside between 1994 – 98 for a disabled husband, his wife and two children. The central aim was to give access to the disabled client at all levels. Instead of simply installing a lift, architects OMA created a 3 x 3.5m mobile platform in the middle of the building – essentially an extra room, complete with office furniture, which could inhabit any part of the house: adjoining the kitchen on the first level, the living room on the second, and the master bedroom at the top.

Two years after completion, the mobile office was transformed by the Zak cushion – a three metre square inflatable silver cushion. We have acquired the silver cushion which you can see at the entrance to the display, and gives some idea of the size of the moving platform.

From The Roundhouse to historic swimming pools and an Olympic Village

I’m an architect first and foremost, but also I’m a disabled person. That means I wear two hats, one is a professional hat and one is my life experience hat.

You can read more about architect David Bonnett’s projects here (comes with BSL, subtitles and a film, which also appear in the Without Walls exhibition). He describes his personal and professional journey to embracing inclusive design, and describes some of the projects he has worked on, including the Olympic Village and Ironmonger Row Baths. These describe how its possible to get a building that works for everyone, whether it is a new build, or the restoration of a space that has already existed for a century or two.

Hogeweyk Dementia Village

Residents in care facilities in the Netherlands averagely exercise only 96 seconds per day. Hogeweyk Dementia Village was created so that everyone had the opportunity to use a beautiful and safe physical space. Each house has a private garden, and there are several communal outdoor areas.

The LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, San Francisco

This building, created in 2016 is the newest in the exhibition and in our history. In it, design materials and how you orient yourself in the space are intertwined: corridors are concrete, stairs are wooden, and social spaces are carpeted.

Design, exceptional cases and privilege

Underlying the exhibition, there is a question of what represents an exceptional, stand out set of circumstances, and what has become truly mainstream. Very few disabled people can have any hope of designing and commissioning their own home, like the owner of Maison à Bordeaux, and although Maggie and Ken Davis were not privately wealthy when their exceptional determination eventually led to the creation of Grove Road, more than 40 years later disabled people without large resources are still having to fight to live independently.

However, there’s a counter-current too: of at least some disabled architects and designers blending their life and professional experience to create better buildings. Public buildings from swimming baths to work campuses are being designed with disabled people in mind. Processes for genuinely including the experience and suggestions of disabled people who are not architects into building design are also becoming more common.

As David Bonnett comments, it is so often the case that in building an environment that works for disabled people, you design a space that also works better for everyone else. V&A’s exhibition shows that there is no lack of role models or well designed buildings. The task for the future is to insist that these ideas become widespread and standard.