This short film also appears as part of Without Walls at the V&A until 21st October 2018.

“I’m an architect first and foremost, but also I’m a disabled person. That means I wear two hats, one is a professional hat and one is my life experience hat.

When I was first an architect, for the first ten years or so, I was completely oblivious of inclusive design. But in 1985 or thereabouts, everything changed because for designers new legislation appeared that required us to consider people with disabilities. The question was: how were we going to do that?

There’s all sorts of technology in place there – swimming pools that we don’t have to climb steps down into. The bottom of the pool comes up to greet us. Isn’t that wonderful?

When looking at buildings, particularly historic buildings, you realise they were made or designed for people who were fit and able – there was no consideration, even in many hospitals, to people with disabilities. Since regulations and legislation and so on were introduced to the architectural profession that control how buildings are designed, we’ve had an abundance of guidance, books and other publications to inform designers – but that is no substitute for personal experience. Particularly with disabled people, with their own knowledge of those buildings, their strengths and their weaknesses, bring that discourse to the table.

Designing the Olympic Village

This was done incredibly well at the Olympic Village by a. insisting that designers as professionals listened, but secondly and most importantly by setting up a group of disabled people from the area – the Disabled Access Group – we needed to appoint people, it needed to be taken seriously and professionally, with that group learning how to conduct themselves and express their opinions to best effect, in front of planners, designers, developers, and so on. That is quite a challenge. And how do you explain a complicated drawing to somebody who doesn’t read plans? How do you explain that to someone who might be blind or partially sighted, unable to see?

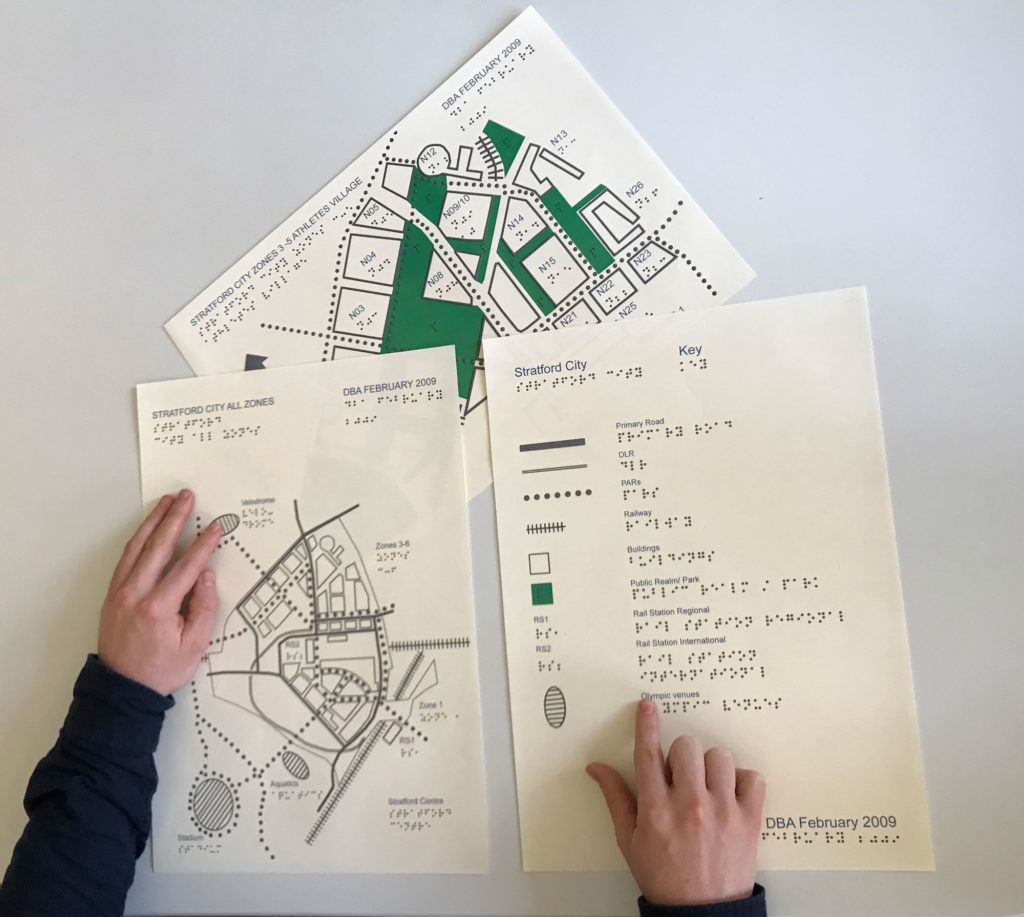

Simplified architectural plans – used by visually impaired people – and found useful by many others contributing to the design of the Olympic Village

Tactile plans

What we developed was what we called tactile plans, where you eliminate all the abundance of detail that’s not necessary, to explain the basic story. You minimise the drawing and then you print it in a way that allows blind people to read those plans. But if you think it’s just blind people who benefit, you’re wrong. Because the plans are so simplified you find an awful lot of other people say, “well thank goodness we’ve got these plans too.”

Unlike in the past, we would select a few buildings for disabled people and all the rest would be for normal people. The question is, who are “normal” people? If you have a disabled champion as part of your design team, the role of that person is to ensure that these important considerations at the beginning of a project aren’t lost upon the way. So in the end you deliver what it is you set out to deliver.

Ironmonger Row Swimming Baths

A building of real interest that we are involved in is known to Londoners as the Ironmonger Row Swimming Baths. Well it wasn’t just a swimming baths it was a public baths, it was a laundry, it was where people went for their ablutions in the days when we didn’t even have bathrooms and physical fitness was only just beginning to come onto the agenda. That building was under threat and it might have been lost, unless it could find a new way of functioning which includes not just for people who are fit and able, but for people who aren’t. That’s older people, that’s disabled people. We are pleased to say we were involved with that to come up with bright ideas, to work with the designer, with Tim Ronalds the architect, to make that building have a future – and we did.

The swimming pool floor that comes to meet you

There’s all sorts of technology in place there – swimming pools that we don’t have to climb steps down into. The bottom of the pool comes up to greet us. Isn’t that wonderful? Makes life easier for all of us, including children. So a question we must ask is how we keep inclusive design on the agenda in the future years because it’s competing with lots of other social considerations – of course it is, quite rightly so, too. And we must rely in part on Government for this, our corporations, our public structures, but also the design profession and people finding a voice.”