In 2013, the University of the Third Age (U3A) carried out a study in collaboration with Langdon Down Museum “to augment its historical database on how Normansfield operated and the people it cared for.” History of Place has been granted permission through the generosity of U3A and Langdon Down Museum to reproduce some of the results of that research. This is the fifth of those case studies, and the third taken from the later years of Normansfield Hospital, up until its closure in 1997. The text below is taken directly from the U3A research pages of the Langdon Down Museum of Learning Disability website, and was written by Tony’s brother, Trevor Hudson.

Tony entered Normansfield at the age of 6 on 21 July 1945, and remained there until it closed 51 years later in 1997. He arrived as the war ended when it was run privately by Dr Reginald Langdon Down, a son of its founder, and left when the NHS, which had taken it over, transferred the residents to care in the community. During this period there were no significant personal events whilst he was supported by caring staff and regular visits by members of his family.

Early Life Before Normansfield

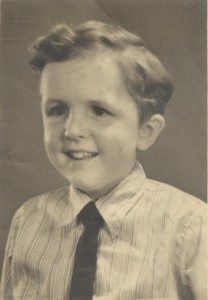

Tony was born on 7 March 1939 just before the outbreak of war, the youngest of four boys, and into a family with no health problems or record of disability. The family home in Essex was requisitioned and they were evacuated to an old thatched house in Chideock, a small village by the coast near Bridport in Dorset. A nanny went with them whilst their father remained behind to continue his business of manufacturing in North East London. He visited during the blackout at weekends, when he could. Many happy days were spent on the beach where they were given special permission because of the coastal defences against possible invasion. As the war came to an end, the family returned to their home in Essex. By now Tony’s three brothers were all away at boarding school and it was noticed that he was not speaking nor acquiring the basic skills of a six year old, but he was placid and cheerful. Dr Paul Sandifer,a neurologist at Great Ormond Hospital, was consulted. No clear diagnosis was made apart from failure of brain development from possible hydrocephalus. He had a large head and the presence of bilateral talipes, club foot, requiring calipers. He recommended that Tony should go to Normansfield.

Normansfield

Tony started at Trematon, a large Georgian House on the Normansfield estate near the river. His mother visited him regularly, usually taking him out to tea with his aunt and family who lived in Twickenham. Her affection and care for him never varied all his life and was no different to that of her other sons. He was never neglected just because he was no longer at home. Having been orphaned in childhood herself, this made all her children the more precious to her. When she died of cancer aged 66 years, her second son Trevor, a GP in London, took over the visiting.

When the NHS took over Normansfield in 1951, Tony was assigned to an amenity bed at a charge of one guinea (£1.10p) a week. Dr Reginald Langdon Down still visited especially on sports days, but had no authority. Parts of the estate were sold off and single storey units were built more suited to the residents’ needs, with large open dormitories and more accessible facilities. Tony moved to Elm House, where he stayed until it was closed down. More seriously disabled residents started being admitted to whom Tony became very attached. This showed a very compassionate side to his nature.

Tony fractured his left ankle leaving him with a deformed leg and restricting his mobility consistent with his childhood talipes. When determined, as he could be, he would walk long distances in spite of it. He loved being taken out for trips locally to Bushy Park or along the riverside, being very aware, in spite of no speech except the odd word like “car” and “yes”. He attended the workshop doing manual tasks and joined in musical events, such as dancing, always brightening up with a smile. He had a voracious appetite, especially for anything with chocolate. His health remained largely unaffected during these years and he was popular with the staff due to his friendly and affectionate manner. But his ability to speak and learn skills never improved in spite of the help he was given.

After Normansfield

When Care in the Community was established by 1997, Normansfield closed down and the residents were moved out into homes locally, each converted to receive only a limited number of about 4-6 residents. Tony went first to Kneller Road, Whitton, for 18 months and finally to 52, Lion Road, Twickenham. He had his own room for the first time, with his bed, furniture and personal belongings and a privacy which he had never known before. He responded very well to the closer contact with staff, therapists, activities and more freedom. His favourite place was to sit in his wheelchair in the hall and watch everyone moving about. He had an advocate who took him out locally to the pub, the cinema and on trains. He was taken on holidays to Spain, Portugal, Brussels on Eurostar, and the Isle of Wight. This was very good for him and also the staff. His placid character made him popular with those around him.

When Care in the Community was established by 1997, Normansfield closed down and the residents were moved out into homes locally, each converted to receive only a limited number of about 4-6 residents. Tony went first to Kneller Road, Whitton, for 18 months and finally to 52, Lion Road, Twickenham. He had his own room for the first time, with his bed, furniture and personal belongings and a privacy which he had never known before. He responded very well to the closer contact with staff, therapists, activities and more freedom. His favourite place was to sit in his wheelchair in the hall and watch everyone moving about. He had an advocate who took him out locally to the pub, the cinema and on trains. He was taken on holidays to Spain, Portugal, Brussels on Eurostar, and the Isle of Wight. This was very good for him and also the staff. His placid character made him popular with those around him.

The last few years of his life showed a steady deterioration in his mobility. His arms and legs became contracted, he developed a tremor and had epileptic fits which were controlled with medication. He became confined to a reclining wheelchair and required hoisting for which special facilities were provided. This in turn led to difficulty in swallowing food and to chest infections. It was one of these infections that required admission to hospital where, after two days, he died peacefully in the presence of one of his carers.

The care which he received during all this time was outstanding. In particular the manager and staff at Lion Road, his many therapists, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist and aroma therapist, who all gave him such personal care. One of his carers, Brenda Bridges, “B”, had looked after Tony for 15 years. He needed little attention from nurses and doctors.

His funeral was held locally and was well attended by staff, family, friends and residents in wheelchairs. It was a reflection of the fond regard so many people had felt for him and the way in which he coped with his disability.

Postscript

Tony was buried at All Saints Church, Epping Upland, Essex, beside his mother and father. He left a legacy which included restoration of the ancient church clock there. The legacy also helped with the documentation of the extensive Langdon Down archive for future research.