One of the fascinating things for me about the History of Place project is the rise, and sometimes fall, of quite impressive architecture. Many of the eight sites we are exploring were built by rich and powerful people (or by the collective will of the public) in response to a strongly held ideal – sometimes religious, sometimes fired up by genuinely progressive ideals about how deaf and disabled people could find a place in society.

When ideas and attitudes move on, the architecture associated with them can become a white elephant, and may be demolished. Our buildings survived – but often diminished, or changed to new uses by history.

In search of Maison Dieu

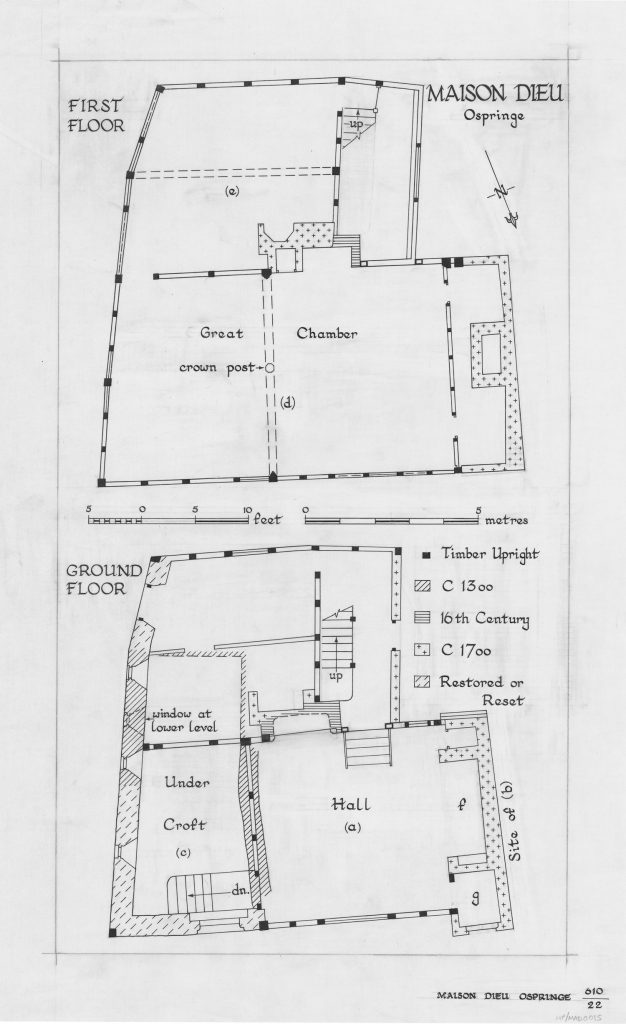

Labelled sheet of plans of the Maison Dieu, showing the ground- and first-floors, with a key to historic building periods. Drawn sometime between 1953 – 1963

Maison Dieu was commissioned by Henry III in 1234, and we no longer know exactly what it looked like when it was a large spiritually and economically important centre on the pilgrimage route to Canterbury. We can only start to see it in early photographs now held by Historic England, from around the 1880s onwards. The images we have here are just a tantalising glimpse, but we can see that the building was still changing with history, even between its 650th and 750th years. This architect’s plan, from somewhere in the decade after 1953, meticulously notes how different parts of the surviving building were added or repaired at different times. Some parts of the 13th century structure remain, but there are 16th and 17th century add ons too.

Creating the first village museum

Maison Dieu – taken somewhere between 1880 – 1920. This image appeared on the front of an appeal for funds to help convert the building into a museum.

This sepia image taken somewhere between 1880 – 1920 is the oldest photograph we have been able to find, with the building looking a little down-at-heel. This picture was used on the front of an appeal for money to turn Maison Dieu into the first ever village museum: it became one in 1923.

This is Maison Dieu in 1941 – we see the marks of war in the taped-up windows against air raids, and spot the passing of time in the clothes worn by children playing outside. We haven’t been able to find out so far why the stonework of the lower ground floor had been replaced by shop windows (at first glance it looks a bit shocking by modern standards of conservation).

A picture showing the upper room of Maison Dieu, clearly during some building repairs on 1st August 1952

In this image of the upper floors of the building, it really does look like a bomb has hit Maison Dieu. But no, this is actually taken in 1952: there’s no explanation with the image, but it seems likely that repair work is taking place.

Finally, here’s the snap taken by my colleague Francesca in mid 2016, with the building wrapped in an appropriately mysterious early summer morning fog. The colour photography picks up for the first time the sheer variety of building materials used over time – from stone, to wood and wattle and daub, to red brick. We have seen it negotiate its way through the perils of two world wars and be embraced by the rise of the heritage movement.

But behind the hundred years we can see were six more, increasingly elusive. If you know of any further traces of Maison Dieu’s past, do tell us.