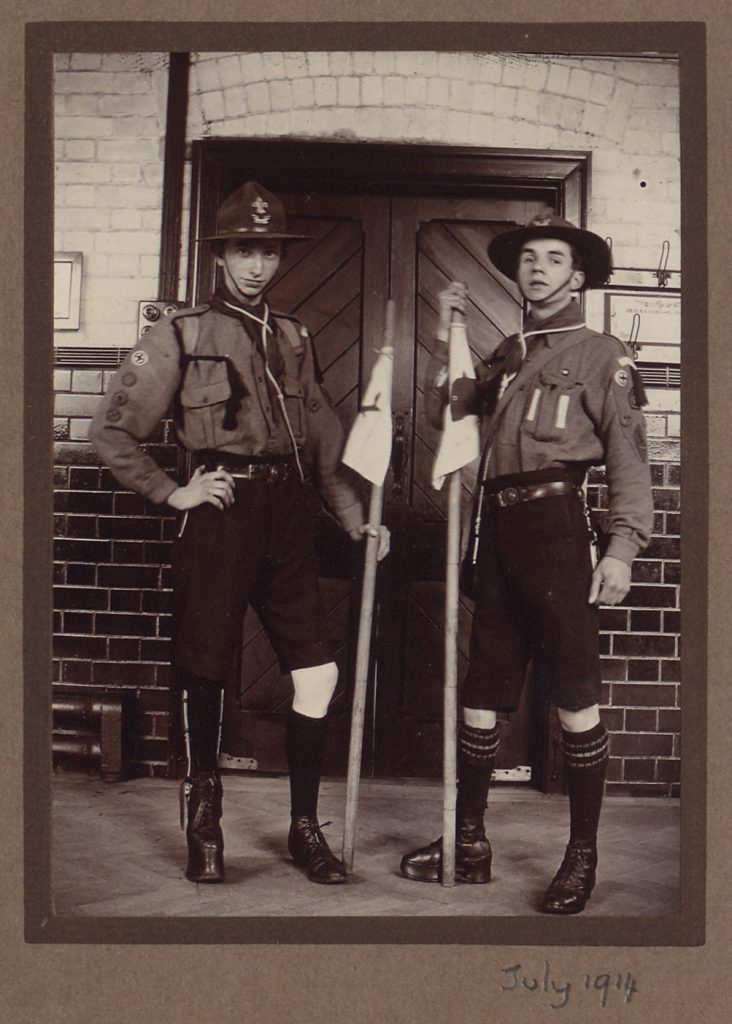

When looking at the Guild’s photo album from the period around 1914, one of the striking things is the ubiquity of the Union Jack in so many outdoor group photographs and dozens of boys of all ages in scout groups. Although the scenes from Bristol and the Somerset countryside show work, leisure and community, national pride and the pressure of war are implicit in the images.

This modern flag made for the exhibition reflects how the crutch crossed with a sword were set at the heart of the Guild’s iconography.

How did the Guild – which had opened its iconic accessible building the year before the war – react in a society on a war footing, and how was it and its members perceived?

From its beginning in the 1890s the Guild had used military analogies in its symbolism – a crutch crossed with a sword sits at the heart of its ‘logo’. It emphasises that its members were not in retreat from the world – like so many in asylums and institutions – but seeking a place in the world.

Ada Vachell wrote:

“If you would come to the ‘Heritage’ on a Guild afternoon, we would show you our regiment – a regiment whose ranks are not open to the able-bodied, but to the disabled”

The scout groups – often pictured in the open countryside at the Guild’s holiday home in Churchill, Somerset showed that Baden-Powell’s enormously popular vision of adventure and self-reliance was something that boys from the Guild could claim and participate in too.

To some extent the two World Wars of the first half of the 20th century transformed how disabled people were viewed. Still a two-tier system was visibly in place, with those disabled in the army more likely to claim work post-1918 than those whose impairment was not the result of war.

You can explore more pictures in excerpts from the Guild’s First World War photo album here.