During the turbulent Civil War years in England, the future of the hospitals and almshouses in Canterbury must have felt decidedly wobbly. Like the Reformation of the 16th century, property and lands owned by the Church were vulnerable and liable to be seized amid such political and religious conflict.

He did not subtract from the pietance of the poor, nor use any arts to rob the spittle; but was tender of their persons, and zealous of their rights.

Step forward one William Somner, a scholarly historian type (and all-round good guy it seems) born and educated in Canterbury. With a fierce dedication to preserving the city’s heritage, Somner played an important role in protecting both the archives and fabric of Canterbury Cathedral, and the rights of the residents of St John’s and St Nicholas hospitals.

Somner was born in either 1598 or 1606 (depending on whether you believe church records or his wife) at 5 Castle Street, Canterbury. The building remains today and bears a plaque commemorating his life. After studying at the free school in Canterbury, Somner became clerk to his father who worked at the ecclesiastical courts of the diocese. In the following years Archbishop William Laud made him registrar of the courts. Here Somner was also able to indulge his passion for history and over the years become a respected antiquarian scholar.

Work as a historical scholar

His first published work was The Antiquities of Canterbury; or a Survey of that ancient Citie, with the Suburbs and Cathedral in 1640, dedicated to Archbishop Laud who was a collector of ancient manuscripts himself. With access to the original charters and numerous other primary sources, Somner put together an impressive history which contains detailed information about the foundation of the Canterbury hospitals as well as the city’s wards, suburbs, churches, gates and other buildings. The book is considered the best of its time for accuracy and depth; and many local history books written in the succeeding centuries used Somner’s research.

In 1648 he wrote A Treatise of Gavelkind (which wasn’t published until 1660), an exploration of an ancient Kentish land inheritance custom. Somner contributed to a number of other books including William Dugdale and Roger Dodsworth’s Monasticon Anglicanum for which he provided information on Canterbury and the religious houses of Kent.

‘Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum’

Somner’s most famous work was the Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum, the first Anglo Saxon dictionary, published in 1657. As a Professor of the Saxon language at Cambridge, Somner built on the work of earlier scholars to translate more than 15,000 words into Old English (Anglo Saxon), Latin and English.

A standoff with the Puritans

Culmer… needed a team of Cromwell’s soldiers to protect him from the locals while he went about his work of stripping Kent’s religious houses of ‘offensive’ symbols.

Being a bit of a traditionalist, Somner was a royalist and admirer of Charles I’s Archbishop Laud – an autocrat who favoured a uniform ‘high church’ brand of Protestantism, considered one step away from Catholicism by Puritans. These views put him in the opposite camp to Oliver Cromwell and the parliamentarians who ousted the King in 1642 – and in the path of one notorious and despised iconoclast, Puritan minister Richard Culmer.

Culmer took great pleasure in carrying out his duties relating to ‘the demolition of superstitious monuments’ and needed a team of Cromwell’s soldiers to protect him from the locals while he went about his work of stripping Kent’s religious houses of ‘offensive’ symbols.

When Culmer was responsible for parliamentary troops attacking Canterbury Cathedral in 1642, William Somner was there to pick up the pieces. He protected ancient Cathedral documents and collected the remains of the demolished font, keeping them hidden in his own home until the monarchy was restored in 1660. The stunning, ornate font (designed by John Christmas in 1638/9) was rebuilt and returned to its home in 1663. It’s believed that Somner’s daughter was the first to be baptised in the reinstated font.

Loathed by Culmer and the Puritans, Archbishop Laud had been arrested by the parliamentarians in 1640 and was executed in 1645. The imprisoned Charles I was executed in 1649.

Imprisonment

In 1659, just before Charles II returned to the throne, Somner and a group of Kent noblemen promoted a declaration for a free parliament:

“We must publish our resentment of our present calamities; our friendlessness abroad and divisions at home; the loud and heart-piercing cries of the poor; the disability of the better sort to relieve them; the total decay of trade; the loss of the nation’s reputation; and the apparent hazard of the Gospel, through the prodigious growth of blasphemies, heresies and schism, all threatening universal ruin.”

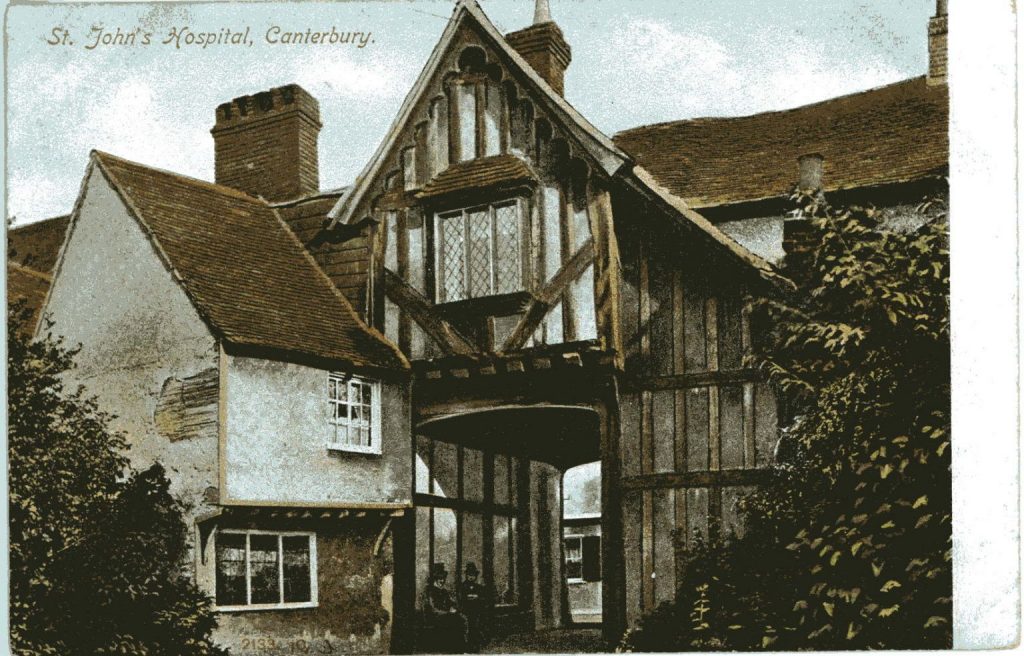

This landed him in prison at Deal Castle, but by Restoration the following year his loyalty to the Crown was repaid with appointments as master of St John’s Hospital in Canterbury, which included responsibility for St Nicholas, Harbledown, and auditor of Christ Church, Canterbury.

Somner’s detective work preserves the almshouses

In these roles Somner devoted himself to hunting down all the relevant records that would reverse the ‘plundering’ of the parliamentarians and reformers, ensuring that property, land and endowments were returned to the rightful institutions.

From contemporary accounts and his long-lasting reputation, William Somner appears to have been an honest, humble and compassionate man who genuinely cared about Canterbury’s heritage.

In the Life of William Somner written by White Kennett in 1693, Kennett said:

“It was his charity, and purity of heart, that prefer’d him to the Mastership of St John’s Hospital, in the suburbs of Canterbury, An. 1660. In which station he did not subtract from the pietance of the poor, nor use any arts to rob the spittle; but was tender of their persons, and zealous of their rights. By his Interest and Courage he recovered some parts of their endowment, of which by the Commissioners on the Stat.37 of Henry VIII it had been fleeced, as other like places, by the sacrilegious pilferies of those ravenous and wretched times. It was for the same plain and open honesty, that at the Restoration he was appointed Auditor of Christchurch Canterbury…”

William died on 30 March 1669, and was buried in the church of St. Margaret, Canterbury. He had been married twice leaving eight children, and had lived his entire life in the city.