Our exhibition ‘Brave Poor Things: Reclaiming Bristol’s Disability History’ is on at MShed, Bristol until 15th April. It’s the culmination of work by project staff and volunteers, particularly in Bristol Archives. From photograph albums and minute books, letters, newspaper cuttings and objects we have recreated the story of a community of disabled people which lasted for almost a century. It explores how they came together, how they saw their lives, how others perceived them – and what sort of narratives they had to create to find a place in wider society.

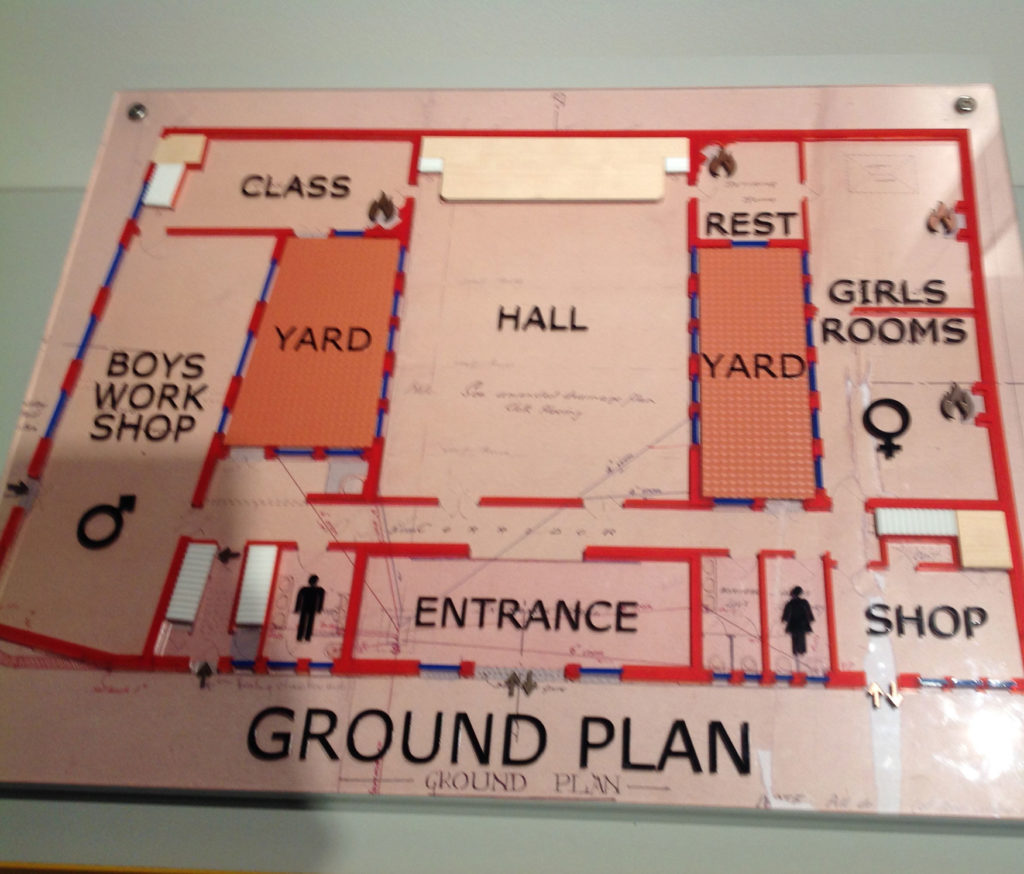

For us, the challenge has also been to create an exhibition that is as accessible as possible – with textured architectural drawings, basketware and beadwork which can be understood by touch or by sight, and with resources in British Sign Language.

‘One of the queerest and most unhandsome of large towns’

Not much is known about disabled people in Bristol in the 19th century, but initially the industrial revolution which enveloped it led to grim living conditions for many poor people.

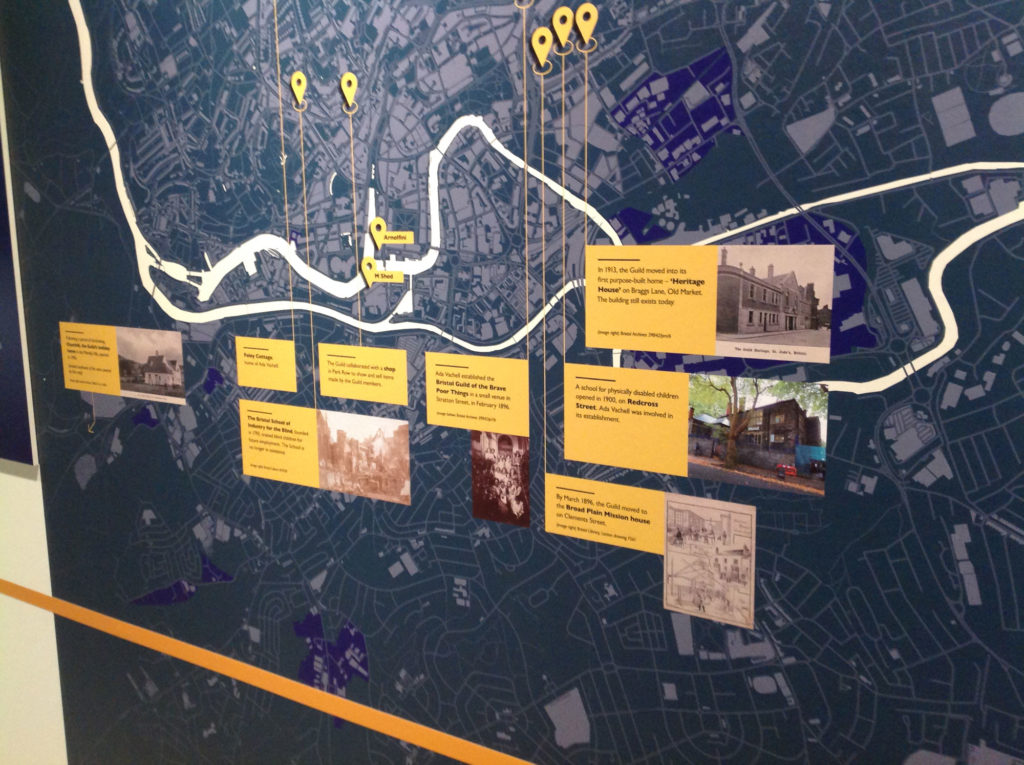

As Bristol began to transform in the 1890s, there was a new impetus to clear slums and create iconic new buildings – and it metamorphosed from ‘one of the queerest and most unhandsome of large towns’ to ‘one of the finest English homes of commerce’. When philanthropists like Grace Kimmins and Ada Vachell formed a community of disabled people it was in the context of a transforming city, intent on slum clearance and social improvement. New architecture was part of the city’s rise, and the Guild’s innovative accessible building built in 1913 was part of that transformation.

As Bristol began to transform in the 1890s, there was a new impetus to clear slums and create iconic new buildings – and it metamorphosed from ‘one of the queerest and most unhandsome of large towns’ to ‘one of the finest English homes of commerce’. When philanthropists like Grace Kimmins and Ada Vachell formed a community of disabled people it was in the context of a transforming city, intent on slum clearance and social improvement. New architecture was part of the city’s rise, and the Guild’s innovative accessible building built in 1913 was part of that transformation.

Escaping the double bind

The exhibition traces individual lives and how they were shaped by wider social forces. When the Great War began, the shortage of labour meant that disabled people were given opportunities to work when they had previously been overlooked. But at the end of the war, returning soldiers were seen as a ‘more deserving’ disabled force, and many Guild members were again thrown out of work. Ada Vachell writes about one man found a profession despite this with help from the Guild:

“When Peace came, he lost his job, and though he tried everywhere and we tried for him, we could not get him work. Always the answer was the same – places must be kept for the returning soldiers. He had a wife and a young family entirely dependent on him… In despair we suggested he should try his hand at toy-making. He has got on splendidly. He makes delightful wooden toys…”

As war veterans disabled in the fighting returned to Bristol, the Guild provided a vital resource in teaching people how to adapt – with some Guild children teaching the men how to recalibrate from their own experiences. Still, the insight that the Guild was a resource seems to have been a transient one: there’s a sense that Guild people still had to prove themselves, and present themselves in the right cheerful, grateful mien to gain acceptance.

In a city of makers

A basket made in the 1940s by William Chapman, a student at the Bristol School of Industry for the Blind.

The first half of the 20th century was a period when the handmade and industrial sat side by side. As well as basket-making and beadwork, which might be practiced alone, many Guild apprentices also found a place in skilled light industry, such as harness making or ‘hand-sewn shoe making’. We think of a career marked by retraining is a relatively recent thing, but its a recurring theme in Guild life stories. Guild members may have needed to be more flexible and inventive to find work and stay in it, and the practical and psychological backup provided in the face of frequent rejection obviously transformed lives.

“Thank God I’m a cripple”

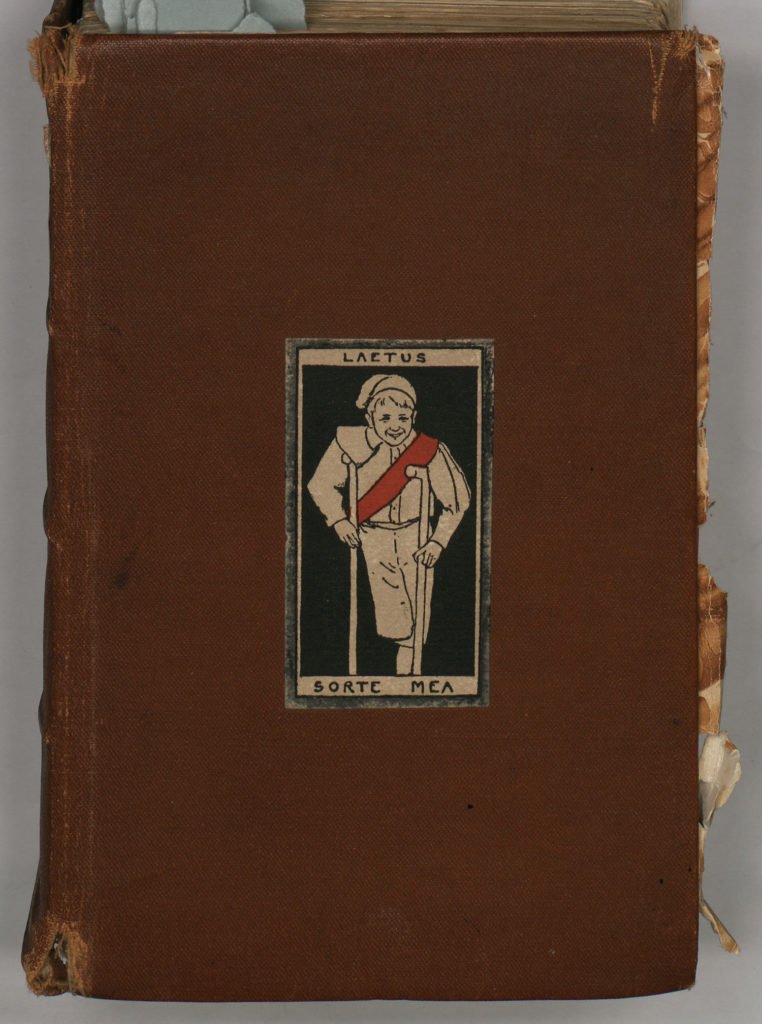

Quotations float suggestively across the exhibition walls, reflecting the different ways Guild members were perceived. For the purposes of fundraising, the image of the deserving poor enduring terrible lives was used pragmatically: a 1905 report says frankly “I have learnt that if anyone wants to go knocking on a heart, it is best to take a little child, best of all a crippled child”.

Sometimes the combination of family poverty and the way society deftly shut some out from opportunity made the ‘terrible lives’ a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially before people joined the Guild: one eight year old is described as being able to fit the shoes of an 18 month old before the Guild fed her up. But there are other voices as well. One member forthrightly describes their disability as the cause of their happiness: “thank God I’m a cripple. I shouldn’t have met [friends in the Guild] if I hadn’t been a cripple”.Things can only get better?

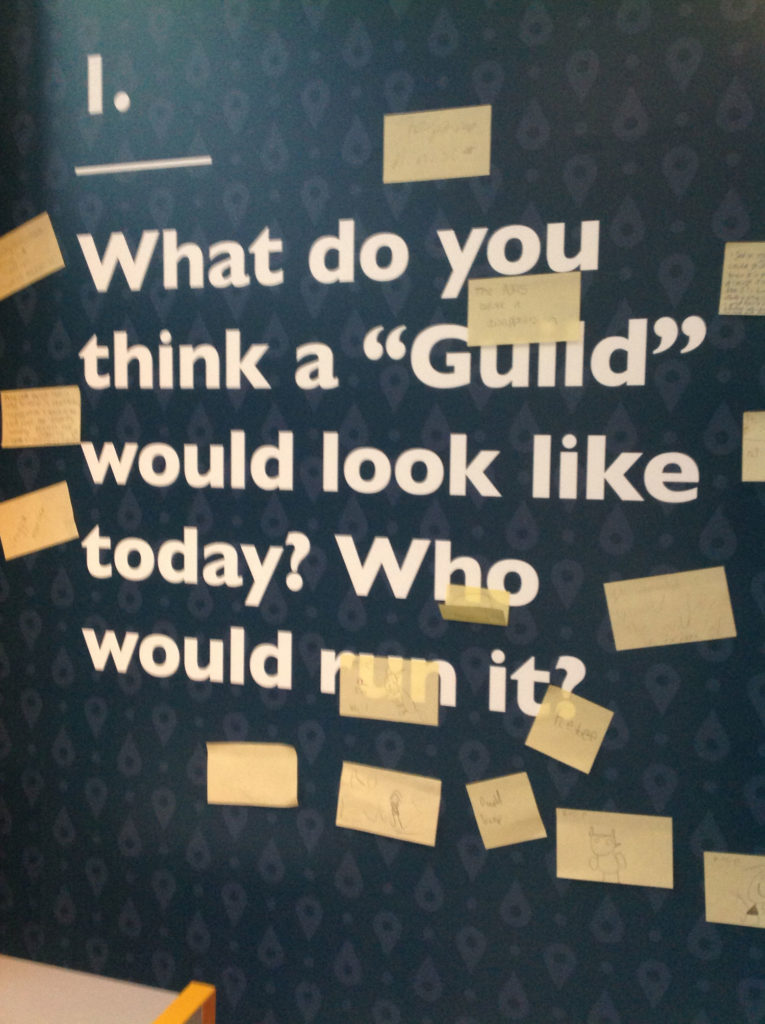

The exhibition ends with questions about the past, present and future experience of disabled people.

Above all, the story of the Guild doesn’t allow us to easily believe that we live in necessarily more enlightened times. A culture where people can come together as a mutually supportive community, and often make beautiful and useful things can seem utopian compared to the early 21st century’s increasingly atomised society, filled with disposable, machine made things.

Disabled people remain far less likely to be considered for work and to face extreme poverty. The exhibition suggests that although we have a rhetoric of empowerment – and some of the language of the Edwardians has dropped away – the reality of the present is often not better, and sometimes worse than a century ago. The final panels of the exhibition invite the visitor to contribute ideas about how far we have, or haven’t come.

Visited the exhibition? Please let us know what you thought in our online survey.