As I perused the Record Book of the Guild of the Brave and the Poor things, which listed all members from 1904 to 1950 and their disabilities, I hoped to find out whether those with ‘unseen disabilities’ such as epilepsy or mental health problems had been allowed to join, or if membership had been restricted solely to those with physical impairments. Within the first few pages I made a surprising discovery: some members were recorded as suffering from ‘Sleepy Sickness’. Could this be, I wondered, a reference to epilepsy or the ‘falling sickness’ a term used to describe the illness for millennia?

Encephalitis Lethargica, a virus-borne epidemic swept through Europe and the US between 1916 and 1927. The virus affected people of all ages causing a plethora of of symptoms from intense lethargy or insomnia, to catatonia and unusual behavioural changes that were often assumed to be schizophrenic.

A quick search revealed that the term ’Sleepy Sickness’ (not be confused with the tsetse fly-transmitted sleeping sickness) was the common name for Encephalitis Lethargica, a virus-borne epidemic that swept through Europe and the US between 1916 and 1927. The virus affected people of all ages causing a plethora of of symptoms from intense lethargy or insomnia, to catatonia and unusual behavioural changes that were often assumed to be schizophrenic. An estimated third of those affected died in the early stages. Survivors exhibited an enormous range of post encephalitic symptoms; from paralysis to being frozen, statue-like in sleep, from the first moment of their illness. It was Oliver Sacks’ experience of trialling a new drug that ‘awoke’ such patients that inspired him to write ‘Awakenings’, an extraordinary account of his work in New York in the 60s, famously portrayed by Robin Williams in 1990 in the film of the same name.

The most intriguing and heart-breaking case histories are of those suffering the most extreme legacy of encephalitis lethargica, but what of people with milder symptoms?

Eagerly I ordered Sacks’ book and pored through the case histories of victims of this peculiar disease. Sacks gives an extraordinary and beautiful account of the explosive awakening of his patients, the tribulations that followed and their eventual decline or, at best, descent into a precarious equilibrium. The most intriguing and heart-breaking case histories are of those suffering the most extreme legacy of encephalitis lethargica, but what of people with milder symptoms? Sacks described an outpatient in London who managed to live a normal life despite having some tremors and paralysis. The Guild members were variously described as ‘paralysed,’ ‘unsteady’ and ‘unable to work’.Their disabilities clearly impacted upon them, yet they were able to attend the Guild. What was life like for them? I needed to get a clearer picture of the encephalitis lethargica epidemic in the UK and more specifically Bristol.

The Northern Daily Mail reported in 1924 that there had been 2,000 victims in 5 months and that the disease was spreading.

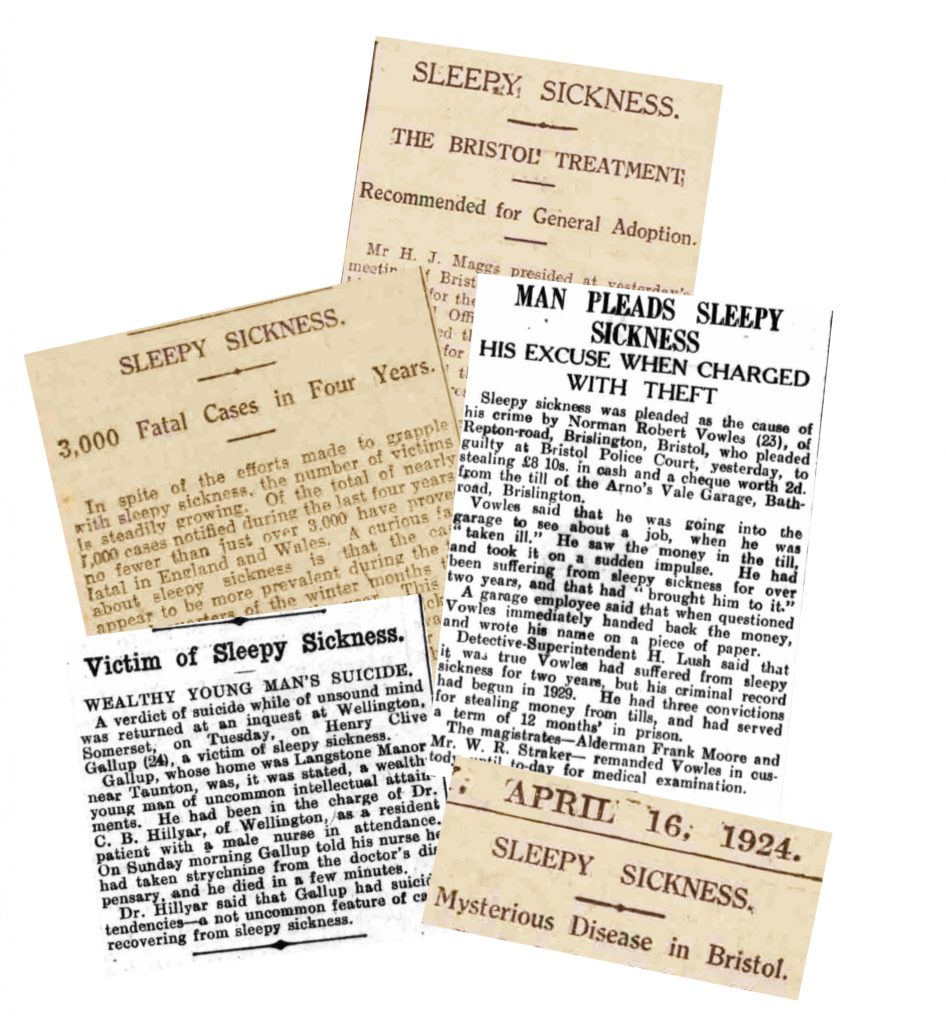

I trawled through the newspaper archive looking for any reference to sleepy sickness and was not disappointed. There were very many articles covering the epidemic throughout the country from 1918 until the late 30s. Outbreaks of encephilitis lethargica were occurring throughout the country, most prominently in Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol and Sheffield. The Northern Daily Mail reported in 1924 that there had been 2,000 victims in 5 months and that the disease was spreading. Some reported on the tragic suicide of victims, others of the moral degeneracy that could emerge in recovery. “ A previously normal sufferer..”reported the Evening Telegraph in May 1924 “…may recover with morals imbalanced and instincts altogether amiss.” 23 year old Norman Vowles, of Brislington, Bristol, wrote the Western Daily Press in 1937, had pleaded guilty to stealing money from a garage till, but claimed to do so ‘on impulse’ after suffering from sleepy sickness for two years. A similar case was reported in Blackpool.

23 year old Norman Vowles, of Brislington, Bristol, wrote the Western Daily Press in 1937, had pleaded guilty to stealing money from a garage till, but claimed to do so ‘on impulse’ after suffering from sleepy sickness for two years.

Despite their best efforts, the medical authorities could not find a cause or cure, and there was much debate as to how to treat the victims. At a conference ordered by the Ministry of Health on this issue in June 1927 Dr Davies, Medical Officer for Bristol spoke about the treatment of sleepy sickness patients at Southmead Hospital, Bristol. The Western Daily Mail reported that there were an estimated 150 to 200 persons in Bristol suffering from late manifestations of the disease in either mild or severe form at this time. In summing up the results of the conference, the Chairman had recommended that the procedures used in Bristol should be adopted throughout the country. Intrigued to know what the ‘Bristol Treatment’ consisted of I sought out the Chief Medical Officers annual reports for 1923-27.

The ‘Bristol Treatment’

Patients were encouraged to partake in healthy open air pursuits, received fruit and cod liver oil on a daily basis and had regular massages to keep up morale.

The reports turned out to be a rich resource covering every conceivable statistic relating to health in Bristol, from the number of recorded infectious diseases to rat infestations. They tell us the number of victims of encephalitis lethargica in each locality, how many died and how many were removed to hospitals and sanatoriums. In the 1927 report I found some details of the lauded ‘Bristol Treatment’. Patients were encouraged to partake in healthy open air pursuits, received fruit and cod liver oil on a daily basis and had regular massages to keep up morale. Given the focus of the Guild on occupational therapies could patients have joined as a means of continuing this treatment? I now knew more about the general situation in Bristol, but with Oliver Sacks’ case histories in mind, I hoped to find out something of the individual experiences of those living with the illness. It was then that I stumbled on the fascinating papers of Dr Bickford.

In search of treatment: Dr Bickford’s detective work

Dr Bickford worked at Fishponds Hospital in the 1950s where he encountered a number of patients who had developed psychotic symptoms after suffering from encephalitis lethargica. To establish better treatment for his patients Dr Bickford decided to conduct a study into all Bristol victims from 1919-1930 to find out the mortality rates associated with the epidemic and the number of those that had suffered psychosis after infection. He began by searching hospital death records, but as a large number had been destroyed in the war, he had to contact 50 local GPs, and other medical staff who had worked with victims of encephalitis lethargica years before asking them to recall the names and case histories of those in their care.

Amazingly, three members of the Guild are listed in Bickford’s papers. Although there were no case histories for them, we are told that one was sent to the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Another is recorded as still alive and living at home in 1951, suggesting that she made a reasonable recovery. Dr Bickford’s papers are incomplete, but include numerous, heart breaking case histories of Bristol patients whose psychotic symptoms and physical disabilities led them into the wards of the Bristol Mental Hospital or to one to of the ‘idiot colonies’ established in the 1930s for the ‘mentally defective’.

Modern cases are rare, and the epidemic all but died out as abruptly as it arrived. It was not until 2004, that two young doctors from Great Ormond Street Hospital published a paper on the probable cause…

Modern cases are rare, and the epidemic all but died out as abruptly as it arrived, yet for many, the physical and mental disabilities left behind lingered for a lifetime. It was not until 2004, that two young doctors from Great Ormond Street Hospital published a paper on the probable cause of encephalitis lethargica: a massive immune reaction to the streptococcus bacteria that causes a sore throat. The paper, printed in an obscure medical journal, received some publicity, but it is astonishing that, despite being so historically recent, and killing millions, the encephalitis lethargica epidemic has been largely forgotten. I hope to uncover more on the every day lives of those living with this curious disease in Bristol and the role the Guild may have played in rehabilitating them.

Brilliant work Grace. Really interesting.

yes, a brilliant piece of research Grace. Just linked into this website as posted by ?your colleague, Dino, on facebook ‘Bristol Then & Now Questions’. I’m passionate about Bristol’s local history, and what with my nursing background, am especially interested in all Bristol ‘Hospitals’ and the districts of St Judes & St Philips.