Read the storyboard version here

Here are the stories Miro chose:

Activism and identity

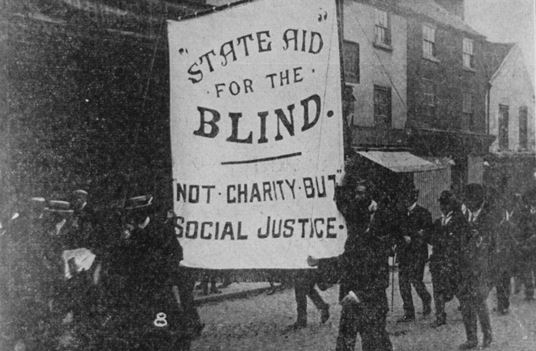

Trade unionist and political activist described as ‘the most cheerful man in the Labour movement’.

Smith’s story prompts us to reflect on the relationship between activism and an individual’s identity. Cultural, political and economic messages associate disability with illness and tragedy, so this is a fascinating example of how an individual shifts the focus away from pity to one of economic and civil rights.

Cultural, political and economic messages associate disability with illness and tragedy, so this is a fascinating example of how an individual shifts the focus away from pity to one of economic and civil rights.

His life and attitude prompted people in 1917 to question the assumptions made about people’s worth within society and drew attention to how disabled people should be part of the education system.

Nevertheless, this attention should not detract from the importance of an individual calling for people to unite and take action. Due to a number of reasons outside of disabled people’s control, we are currently witnessing low levels of united action, diminished numbers of people protesting and fractured social movements across the globe – so this is a useful reminder for how important it is for people to come together and outline the key demands to bring about disabled people’s emancipation.

The politics of disability (over a couple of millennia)

Blog: The Long View – the politics of disability from 6th century China to the Industrial Revolution

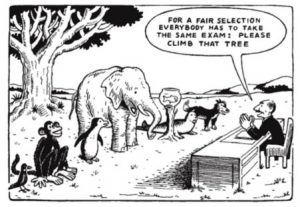

This 1976 Hans Traxler cartoon is usually accompanied by a quote incorrectly attributed to Einstein – “Everyone is a genius but if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree it will spend its whole life believing it is stupid.”

This piece covers a talk by writer Roddy Slorach about his book ‘A Very Capitalist Condition’

This article allows us to consider our understanding of what history means, how we contextualise it within the contemporary and is a useful bridge to consider the macro and micro levels of power and opportunity – it is a useful article to shape our conversation on ‘what we know and what we produce with our knowledge’ rather focus on ‘how do we know it’.

The article also challenges us to consider the significance of history. It draws attention to what was happening, but we are left to consider why it happened and what can we do about it?

Our existence is permanently affected by the fluctuating levels of power, opportunity and resistance. The evidence is overwhelming – disability rights is supported only in so far that it contributes to social and economic objectives. If disabled people’s freedom from exclusion and marginalisation does not fit with the ideas and aspirations of those in power, then our demands are silenced and our presence pushed aside or – in extreme examples – ended.

If we think of the world as a series of events, then we are able to take hope that nothing is fixed, permanent and static – which means positive change can happen but it requires action.

Reflecting on Slorach’s research, I am left thinking that our social world is made up of an endless cascade of events that bring together nature and culture. If we think of the world as a series of events, then we are able to take hope that nothing is fixed, permanent and static – which means positive change can happen but it requires action.

Creating spaces for independent living

This piece describes how Ken and Maggie Smith resisted living in a home after becoming disabled, and spearheaded the beginning of the Independent Living Movement.

Their story shapes our understanding of the relationship between animate and inanimate objects, human and nonhuman contexts – shows us how oppression and marginalisation can go beyond the decisions and demands made by human beings and is inherent within our whole environment; also is an opportunity to explore social activism and how we should see our world as a series of events.

How different is it being a disabled person now compared to 1976?

As I read this article, and reflected on my own experiences as a young disabled person using services throughout my life, I thought about how our understanding of marginalisation and oppression should go beyond the individual. Too often, emphasis is placed on the behaviours and expressive composition of individuals that cause pain, suffering and exploitation; rather, we should be thinking about how our environment – the establishment, continual maintenance and presence of inanimate objects – perpetuates the cycle of exclusion and discrimination towards disabled people.

In this article, Maggie and Ken escape the confines of an institution in 1976; now, in 2017, we have institutions operating and receiving funding across the world, people forcibly placed within day centres because of cuts to services and assessment procedures that dictate individuals must be placed within treatment centres for an indefinite period time. Is this acceptable? Is this notably different from the experience of those from previous generations? Through social activism, prominent social movements, research produced and controlled by disabled people, we can address the structures within our society that reinforce the notion that disabled people are ‘other’, inferior or require specialist, segregated initiatives.

Lives shaped by medical labels

Blog: Violet Elinor Mills

Violet’s story challenges how we tend to think about history. Typically, history is viewed as primitive and contemporary society is advanced and progressive – I, along with many other sociologists, disagree with this. The historical representation of disabled people is one of domination by medical professionals, the emergence of medical labels to dictate how people should live their lives, the implementation of strategies to sterilise, euthanise or terminate disabled people – which period of time am I referring to?

Typically, history is viewed as primitive and contemporary society is advanced and progressive – I, along with many other sociologists, disagree with this.

Pick one, as the statement can apply to numerous periods. Whilst we have the expansion of human rights legislation, extensive debates and conversations surrounding the notion of disability and researchers taking interest, we are fundamentally left with what we believe and know – disabled people’s life chances must be improved.

Learning the lessons of history

This has, hopefully, been an opportunity to reflect on key issues surrounding disabled people’s historical and contemporary position within society. It is useful to note that many of the examples selected have centred upon individuals with physical impairments and health conditions; there is a desperate need to recognise that much of the work surroundingthe inclusion of disabled people’s voice, and a recognition of the activism and campaigning that occurs, is dominated by the work and opinions of those who are white, male, heterosexual, physically impaired and Western educated.

Disabled people have been excluded, isolated and marginalised because they were not considered normal. Now is the time for all of us to disrupt the sense of normality.

If we are to build an inclusive society, by learning from our history and reflecting on our future, it requires methods and the desire to bring the views and experiences of all disabled people – from all backgrounds.

Similarly, our work should always focus on how we want the future to operate. Too often, we remain fixed on the individualised accounts of how we want our, personalised, future to be – but it is paramount that our work, activities and conversations think about the collective. That is a simplified statement for a complex issue but we must think about how we ground our discussions in the ideas for a potential, probable and preferable future. Ultimately, this excellent project has shown that disabled people have been excluded, isolated and marginalised because they were not considered normal. Now is the time for all of us to disrupt the sense of normality.