The first activism to provide education and work for deaf people began in the late 18th century. This led to the creation of the Refuge for Deaf and Dumb founded by the Rev Samuel Smith in 1844, providing training in trades and support for deaf people. Smith was also the first ordained minister to Deaf people and wrote a pamphlet affirming that that sign is our first language.

A service at St Saviour’s Church, Oxford Street, from the Collage archive. Built in 1870 – 4, it was demolished in 1923. Like its successor in Acton, it was built with plenty of light and visibility for sign language.

It was against this background that St Saviour’s Deaf Church was first built on Oxford Street in 1873. Much more than just a building, it became a symbol of the right of deaf people to take a full part in church and society. Smith was involved and baptised some of the congregation there.

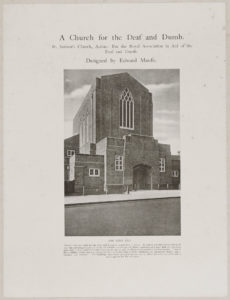

However, it was only when the church found that it had to move to new premises in the early 1920s that there was an opportunity to create a place perfectly shaped to the needs of the community. A site was chosen in Acton and a new building was designed by prominent architect Sir Edward Maufe. It opened in 1925.

View of the front of the church – the caption describes the amenities which include a kitchen, servery and billiard room

The church building itself was designed so that the way light fell made it easy to sign. There were no central pillars in the church, but it contained two pulpits: one for a minister to deliver the sermon in speech and another for sign.

There were also many other buildings in the complex and we can see from these how much the congregation was a tightly knit community which wanted to enjoy a variety of social and leisure activities together.

As well as rooms to be used as offices, classrooms and dressing rooms there was a tennis court, a billiard room with ‘top-lighted tables’, a kitchen and a small garden for the Chaplain.

We know from exploring the records that when one family member, usually a parent, was deaf, the rest of the family would attend St Saviour’s and both children and adults were baptised there. The Bairds, the Carters and the Bones were all families that followed this pattern.

Beyond the walls of St Saviour’s and particularly after the Milan Conference in 1880, sign language was under threat as oralism was chosen (by hearing people) as the best way to educate deaf people. The damage this caused wasn’t really acknowledged until a British Deaf and Dumb Association report in 1970. By contrast, St Saviour’s was a place where the needs of deaf people and the central importance of sign language were not only acknowledged by the Established church, but also manifested in the architecture.

Congregation signing

St Saviour’s finally closed in 2014 due to lack of funding, although the congregation continues to meet at other sites. However, as we discovered at an event we held with congregation in 2016, the building and its community has had a profound effect across whole lives. Some participants now in their 70s described how they had joined the St Saviour’s as teenagers and described their memories from more than 50 years of its history.

Watch: in our short film Stanley (99) and Jovita (13) reflect on the history of St Saviour’s Deaf Church.