We asked academic and activist Miro Griffiths to choose some favourites from the stories we have told in the History of Place project. What do they tell us about the underlying assumptions that disabled people lived with in history – and how many still have currency now? You can read Miro’s comments in the blue boxes.

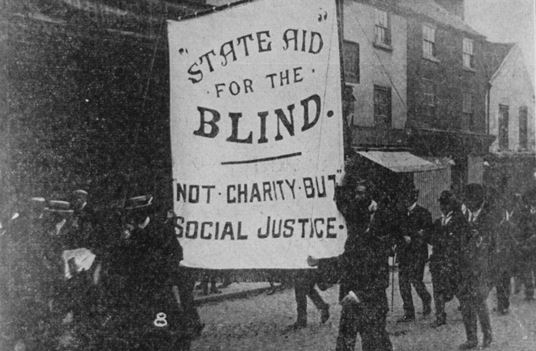

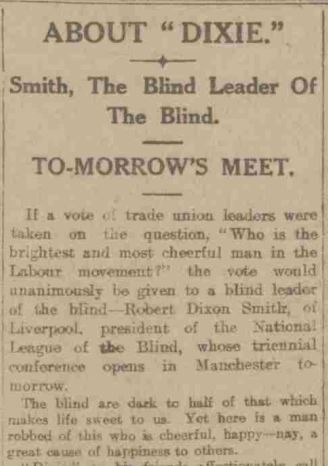

Robert ‘Dixie’ Smith was a trade unionist and political activist described as ‘the most cheerful man in the Labour movement’. He campaigned for blind people to learn a wage to allow them to live with dignity and make ‘blind beggars’ a thing of the past.

Read more about Robert ‘Dixie’ Smith and his activism.

Cultural, political and economic messages associate disability with illness and tragedy, so this is a fascinating example of how an individual shifts the focus away from pity to one of economic and civil rights. It prompts the people of 1917 to question the assumptions made about people’s worth within society and draws attention to how disabled people should be part of the education system.

Miro says...

We are currently witnessing low levels of united action, diminished numbers of people protesting and fractured social movements across the globe – so this is a useful reminder for how important it is for people to come together and outline the key demands to bring about disabled people’s emancipation.

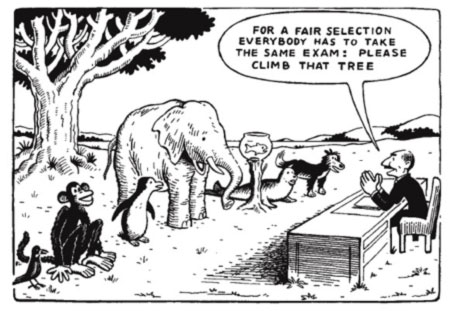

We covered a talk by Roddy Slorach who takes a very long view, and points out that disabled people were present in hunter-gatherer societies, where there was mutual support, and that a turning point in perceptions of disabled people came with urbanisation and industrialisation which gave people less control over their lives.

Blog: The politics of disability: from sixth century China to the Industrial Revolution

History tells us what happens, this piece asks ‘why did it happen and what can we do about it?’ Our existence is permanently affected by the fluctuating levels of power. The evidence is overwhelming – disability rights are supported only when they contribute to social and economic objectives. If disabled people’s freedom from marginalisation does not fit with the ideas of those in power, then our demands are silenced and our presence pushed aside or – in extreme examples – ended.

Reflecting on Slorach’s research, I am left thinking that our social world is made up of an endless cascade of events that bring together nature and culture. If we think of the world as a series of events, then we are able to take hope that nothing is fixed, permanent and static – which means positive change can happen but it requires action.

Our piece on ‘Liberation Architecture’ describes how Maggie Davis did not accept that she would spend the rest of her life in an institution after becoming disabled, but instead campaigned with her husband Ken to live in her own adapted home. With others, they created the birth of the Independent Living Movement.

Blog: Liberation Architecture

Places: Learn more about Grove Road Housing Scheme where Maggie and Ken moved to in 1976

As I read this article, and reflected on my own experiences as a young disabled person using services throughout my life, I thought about how our understanding of marginalisation and oppression should go beyond the individual. Too often, emphasis is placed on the behaviours of individuals that cause pain, suffering and exploitation. Instead we should be thinking about how our environment perpetuates the cycle of exclusion and discrimination towards disabled people.

In this article, Maggie and Ken escape the confines of an institution in 1976; now, in 2017, we have institutions operating and receiving funding across the world, people forcibly placed within day centres because of cuts to services and assessment procedures that dictate individuals must be placed within treatment centres for an indefinite period time. Is this acceptable? Is this notably different from the experience of those from previous generations?

Violet Eleanor Mills is one of a series of people whose lives we uncovered in the archives, who was resident at Chiswick House Asylum. She was admitted aged 21 on 8th July 1924. Various doctors notes describe her condition in terms of ‘insomnia’ and ‘inappropriate remarks’. She was eventually released and lived to 72 on an independent income.

Blog: Who was Miss Violet Eleanor Mills?

Places: When Chiswick House was an asylum

Do things get better as history progresses?

Typically, history is viewed as primitive and contemporary society is advanced and progressive – but how differently would Violet be treated today? The historical representation of disabled people is one of domination by medical professionals, the emergence of medical labels to dictate how people should live their lives, the implementation of strategies to sterilise, euthanise or terminate disabled people – which period of time am I referring to? Pick one, as the statement can apply to numerous periods.

The future: disrupting the sense of normality

I hope my choices have raised key issues surrounding disabled people’s place in society, past and present. Many of my choices have centred upon individuals with physical impairments and health conditions; much activism is dominated by the work and opinions of those who are white, male, heterosexual, physically impaired and Western educated. If we are to build an inclusive society, by learning from our history and reflecting on our future, we must include the views and experiences of all disabled people – from all backgrounds.

Our work should always focus on how we want the future to operate. Too often, we remain fixed on the individualised accounts of how we want our, personalised, future to be – but we must think about the collective. We must ground our discussions in the ideas for a potential, probable and preferable future. Ultimately, this excellent project has shown that disabled people have been excluded, isolated and marginalised because they were not considered normal. Now is the time for all of us to disrupt the sense of normality.