Who was Arthur Knowles?

Manor House asylum in Chiswick became a home-from-home for many of its affluent guests, one of whom, Arthur Knowles, was a regular voluntary boarder during the 1890s. He was admitted as an inmate at least four times, as recorded in the flowing hand of Dr Charles Molesworth Tuke, who shared the position of medical supervisor of the asylum with his brother Dr Thomas Seymour Tuke at this time.

The second son of a large Victorian family in Streatham, South London, Arthur was one of 13 children. He had been expected to join the family business headed by his merchant father, but began to experience “choreic spasms” (see here for an explanation of this term) in his arms and then epileptic fits at an undisclosed but early age. Although he could go months without any fits, by his early ‘20s he had given up any hope of working in the city office.

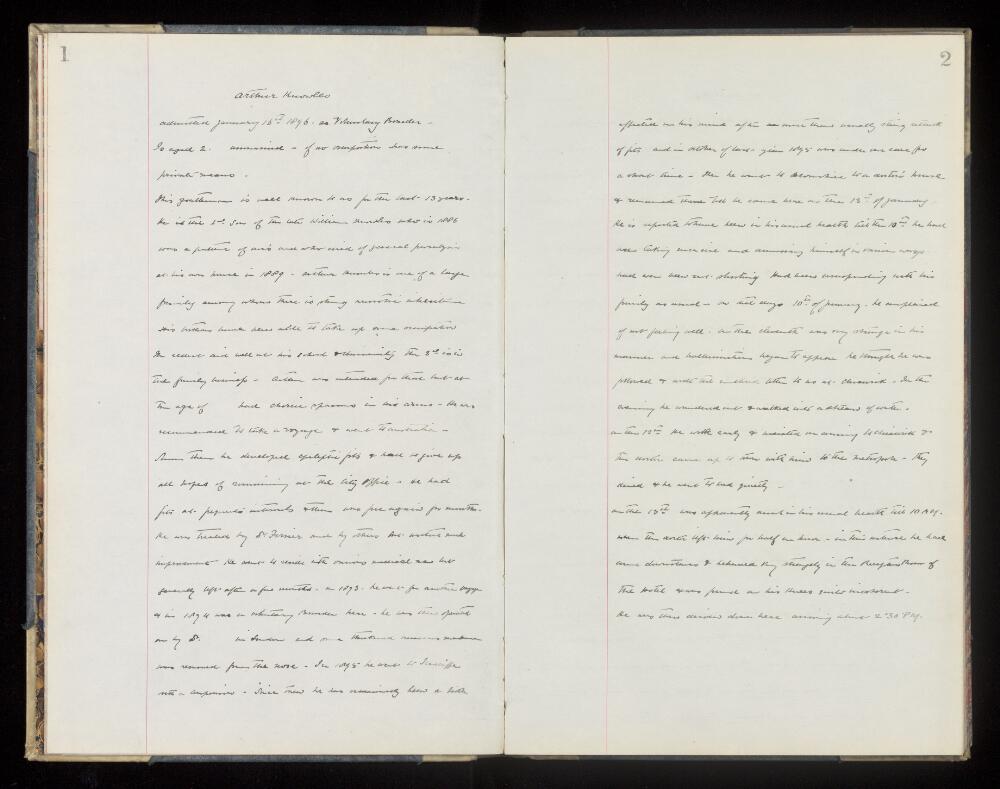

Tuke’s notes in the archive begin in January 1896 when Arthur had been admitted for the third time as a voluntary boarder, at the age of 25. By this stage he had experienced more severe fits at intervals and was feeling increasingly “affected in his mind”.

In the days leading up to his admission, Arthur had suffered hallucinations and believed he was being followed. After feeling unwell and wandering into a stream he asked his aunt (with whom he was staying) to take him to the Chiswick asylum. During their journey he was found incoherent on his knees in the reception of the luxury Metropole Hotel where they were guests.

Arthur is described as having dark hair and dark eyes with long lashes (“much like his late father’s”) and “…expression very vacant. Smiling vaguely and though he thanked me and knew where he was he rambled on in a maudlin condition. His gait was shaky and weak……had passed water in his clothes.” He was given a warm bath, put to bed and later brought some soup.

Family History of Illness

The Knowles family were already well known to the staff at Chiswick. Arthur’s father William had been a patient in 1886, aged 45. There are pages and pages of notes about William from that time: having no previous “attacks” he was at that point clearly suffering from serious mental health problems as well as fits and other physical symptoms. William’s condition deteriorated over the next few years and he was finally discharged as “not improved” in August 1889. According to the notes he died on 6 November 1889 of “general paralysis” at his home.

Both Arthur and William’s symptoms hint at more than mental health issues, with muscle spasms and epileptic fits featuring heavily too. In his notes, Charles M Tuke refers to there being “strong neuristic inheritance” within the family, though this diagnosis, related to the now discredited theory of ‘vitalism,’ should no longer be relied upon.

Originally I believed it was possible that Arthur and William Knowles were suffering from a condition now known as Huntington’s Disease (HD). The disorder was first recognised in 1872 in the US but remained poorly understood for a long time. HD is a fatal disorder of the central nervous system, caused by a faulty gene inherited from a parent. Chorea (jerky, involuntary movements) and dystonia (muscle spasms leading to unusual twisting or postures) are significant symptoms of the disease, along with cognitive problems and psychiatric disturbances.

We now know that most people develop symptoms between the ages of 30 and 50, but between 5% and 10% with HD develop symptoms before they are 20. The majority of those who have juvenile-onset HD experience more severe symptoms and have inherited the condition from their father. The disease steadily worsens so that a patient becomes completely dependent on others and eventually dies.

Nowadays someone with HD can expect to live from between 10 and 25 years after they first display symptoms. The usual causes of death are infections such as pneumonia, malnutrition (feeding becomes very difficult) and heart failure. Suicide is also very common.

Running in the Family?

A fews days after researching HD, I came across the term general paralysis again. It turns out that this phrase (or the slightly more chilling “general paralysis of the insane”) was used in the Victorian era almost exclusively to describe the late stages of the sexually-transmitted disease syphilis (neurosyphilis). Although a general connection between those with a ‘debauched’ lifestyle and a particular kind of mania had been made early in the 1800s, it wasn’t until the end of the century that a direct link was recognised between the condition and syphilis.

the term general paralysis…was used in the Victorian era almost exclusively to describe the late stages of the sexually-transmitted disease syphilis

Looking back at William’s patient notes, his symptoms certainly match those of someone suffering from neurosyphilis: grandiose plans and delusions of grandeur, shouting and aggressive behaviour, restlessness, one unusually dilated pupil, seizures, an unsteady gait, no history of drinking (sometimes alcoholics were misdiagnosed with the illness) – and ultimately a debilitating decline to death.

It is thought that 15% of men in English psychiatric hospitals were suffering from late-stage syphilis during this period.

And what about Arthur? Could he have been suffering from congenital syphilis passed on to him before birth, rather than HD? I have found no suggestion of this in his case notes, and only a few of his symptoms seem to match up, but it is possible.

Arthur was fortunate that his family seem to have been very supportive and could afford to provide the best care available to him at the time

Whatever the cause of his health problems, Arthur was fortunate that his family seem to have been very supportive and could afford to provide the best care available to him at the time. Tuke notes that in 1894 he had an operation on his nose to remove some mucus membrane (one symptom in common with those suffering from congenital syphilis) and describes him visiting a number of medical specialists and also embarking on voyages to Australia, Tenerife and, in 1897, South Africa. Things were going well for him there until a particularly severe fit:

“He tells me there he was unconscious for three days and was “off his head” for ten days after that and “thought he was dead”.

At Chiswick House, Arthur’s treatment seems to have consisted mainly of sleep, warm baths, wholesome meals and a fair amount of cathartic drugs to get his bowels moving. He also had the freedom to visit various family members in London when he was well enough.

Today there is still no treatment that can stop or reverse HD but patients are given a combination of medications and therapy to try to keep the distressing physical and mental symptoms under control. Anti-depressants, anti-psychotic drugs, tetrabenazine for the movement disorders, physiotherapy and speech therapy can all help, but the eventual outcome remains the same as in William and Arthur’s day.

For syphilis the story is heartbreakingly different. Since the discovery of penicillin and its widespread use from the 1940s, a simple course of antibiotics can cure this devastating disease before it reaches its final stage.

The last entry in the archived casebooks for Arthur reads: “Nov 9th 1897. A slight fit. This morning in bed at 8 o’clock. Was able to rise and come down to breakfast at 9am as usual. He has been to London to see his brother and Dr Price.”

Arthur’s Last Days and the Family He Left Behind

Searching for more information about Arthur’s life outside the asylum, I discovered that he died on 25 November 1907 in Spaxton near Bridgwater, Somerset, aged about 37 years. I do hope he had his family around him.

Arthur’s mother was Emma Loetitia Paxton, one of the Paxton family which included the celebrated gardener, MP, architect and designer of Crystal Palace, Sir Joseph Paxton. She lived in Bromley until her death in 1924. Emma had married William Knowles on 29 November 1866 in Shoreditch, London. As well as Arthur they had Foster, Lillian, John, Bertram, Ethel, Mabel, Stuart, Eric, Evelyn, Wilfred, Ronald and Harold!

Foster, Arthur’s older brother, studied at Harrow followed by Cambridge University, later becoming a prep school master in Eastbourne. Ronald and Harold Knowles both settled and had families in Ontario, Canada. Mabel went on to write more than 200 books under her pseudonyms of May Wynne and Lester Lurgan, mainly romances and girls’ adventure stories, but most notably one of the first science fiction novels written by a woman, Message from Mars. It’s not clear whether any of Arthur’s siblings had inherited the same disease as he or his father.