We have just added a new set of archive images to our website – all courtesy of Bristol Archives. Unlike our previous set of photographs from around the First World War, many of these contain text, and cast a fascinating light on how the Guild projected itself publicly, what it asked of its members in terms of attitude, and how the values of Edwardian Christianity fitted its brand.

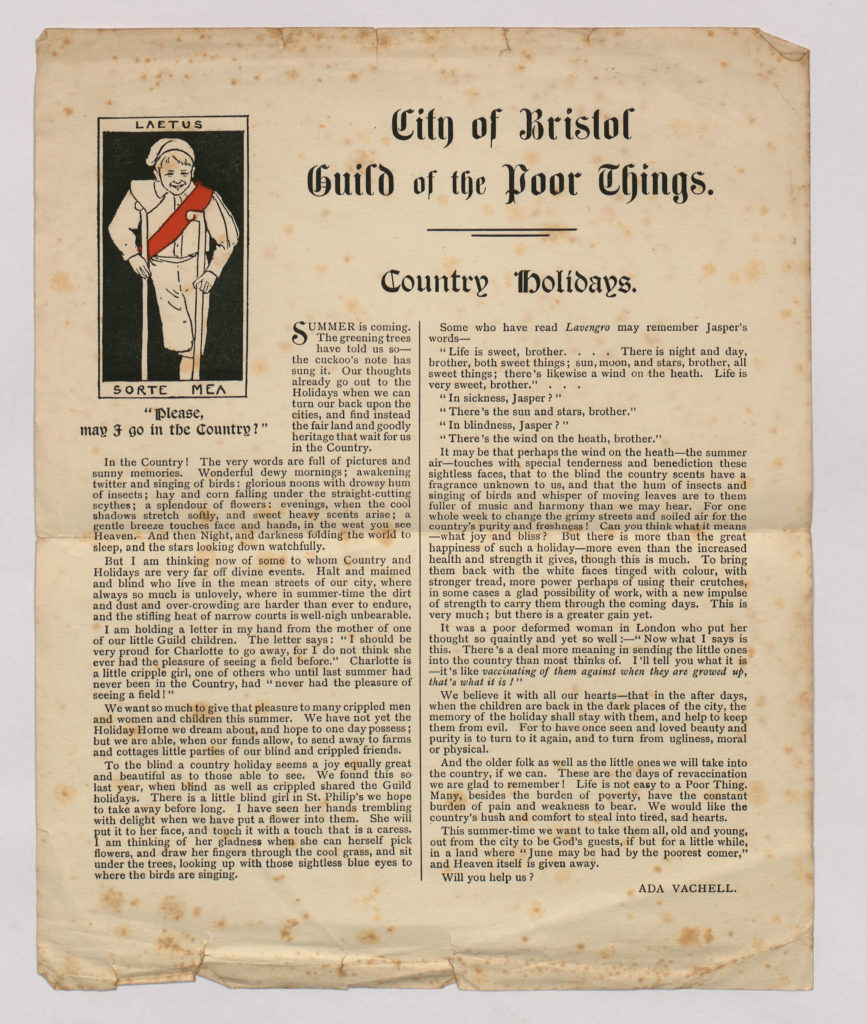

This appeal by Ada Vachell for country holidays for Guild members – particularly children – from the early years of the 20th century is a good example. Industrial Bristol was a ‘smokey’ city, which had health impacts on some Guild members, both because of the fumes and because (as we now know) the natural world is good for mental health. Poverty made it very difficult for many to leave, even for a few days each year.

Ada writes…

“But I am thinking now of some to whom Country and Holidays are very far off divine events. Halt and maimed and blind who live in the mean streets of our city, where always so much is unlovely, where in summer-time dirt and dust and over-crowding are harder than ever to endure, and the stifling heat of narrow courts is well-nigh unbearable.

I am holding a letter in my hand from the mother of one of our little Guild children. The letter says: ‘I should be very proud for Charlotte to go away for I do not think she ever had the pleasure of seeing a field before’. Charlotte is a little cripple girl, one of others who until last summer had never in the Country, had ‘never had the pleasure of seeing a field!'”

The art of appeal

Ada’s appeal is effective – her well-off readers will have been shocked at the idea of a child raised so cut off from the ordinary sights of the natural world. The combination of heavily laid-on sentimentality with stoicism sits more uncomfortably with us now – although if you take away the words we no longer use like ‘halt’ ‘maimed’ and ‘cripple’ it is perhaps less far away from the language and approach of modern fundraising campaigns, especially for children, than it initially appears.

Children at the Guild holiday home in Churchill, Somerset. The caption, from a Guild book, reads ‘I said to myself how nice it is/ for me to live in world like this’.

Not shaking the status quo

The Guild’s ethos is one that fits in an Edwardian Christian tradition of uncomplaining passive acceptance. The appeal is not asking its readers to be angry, or really rocking the social boat by asking why a child should have ‘never seen a field’. Instead it appeals to readers’ sentimental urge to help people who are putting on a brave face, and asking for so little.

In this, Ada was obviously in tune with her society, and a very successful fundraiser: the Guild eventually opened a holiday home in Somerset, and a week or two away in a country environment each year was a great advantage to the Guild’s members.

It could also be argued that an approach that didn’t greatly disturb the mores of the surrounding society allowed the Guild to achieve all kinds of radical things – particularly the Guild building in Bristol itself which was decades ahead of its time in terms of accessibility, and tenacious work to give its members access to employment and nature.

As we’ve argued elsewhere, the Guild’s closure in the 80s was partly due to the rise of State structures for disabled people, but also partly because it maintained an ethos, which had worked so well in Edwardian England, which did not shift much at a time when disabled people were becoming more politicised, and no longer content to have their lives projected as stoical and sentimentalised.