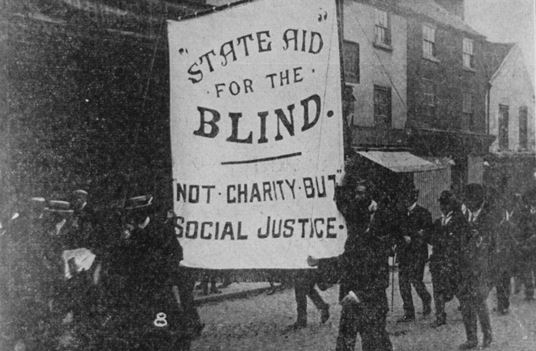

Deaf and disabled people without a private income often had very tough lives in the late 18th century – education and work were often out of reach and destitution was common. A number of pioneers worked to change the culture so that disabled people were not shut out of all opportunities.

However, as we will see, often education and employment designed to improve disabled people’s lives could itself become stigmatised or leave people with a very narrow set of options. Getting a voice in how work and education are structured remains a live social issue.

In the late 18th century there was no provision for teaching deaf children, except in the families of the very rich. One woman spent £1,500 on educating her deaf son, the equivalent of around £100,000 today. Reverend Townsend believed that education could be made available to deaf children regardless of income.

Some had doubted the demand for a charitable institution for deaf children when the evangelical minister Reverend Townsend of Bermondsey first began raising funds in June 1792. Until that point, education for deaf children had been limited to private schools where wealthy families were charged extortionate fees, teaching methods were a closely guarded secret and unpromising students were quietly dropped.

Research by Maxine Clarke

By 1815 the school was hugely oversubscribed with 73 applicants for 17 places, so access to education was still a matter of luck. The school grew, first in London, then moving to an imposing building in Margate, to get away from the polluted capital and benefit from the good sea air. By 1938, there were 418 pupils and 150 staff.

However a conference in Milan in the 1880s changed the course of education for deaf children, favouring lip reading over sign language. In a report 90 years later, the British Deaf and Dumb Association concluded the method had been unsuccessful and made it far more difficult for deaf children to learn.

Wanted, two male and two female teachers for deaf and dumb Asylum. Required to teach orally, must not have previously engaged in teaching signing. No deaf experience necessary.

Minute book, of the Margate Branch of London Asylum (later known as the Royal School for the Deaf, Margate)

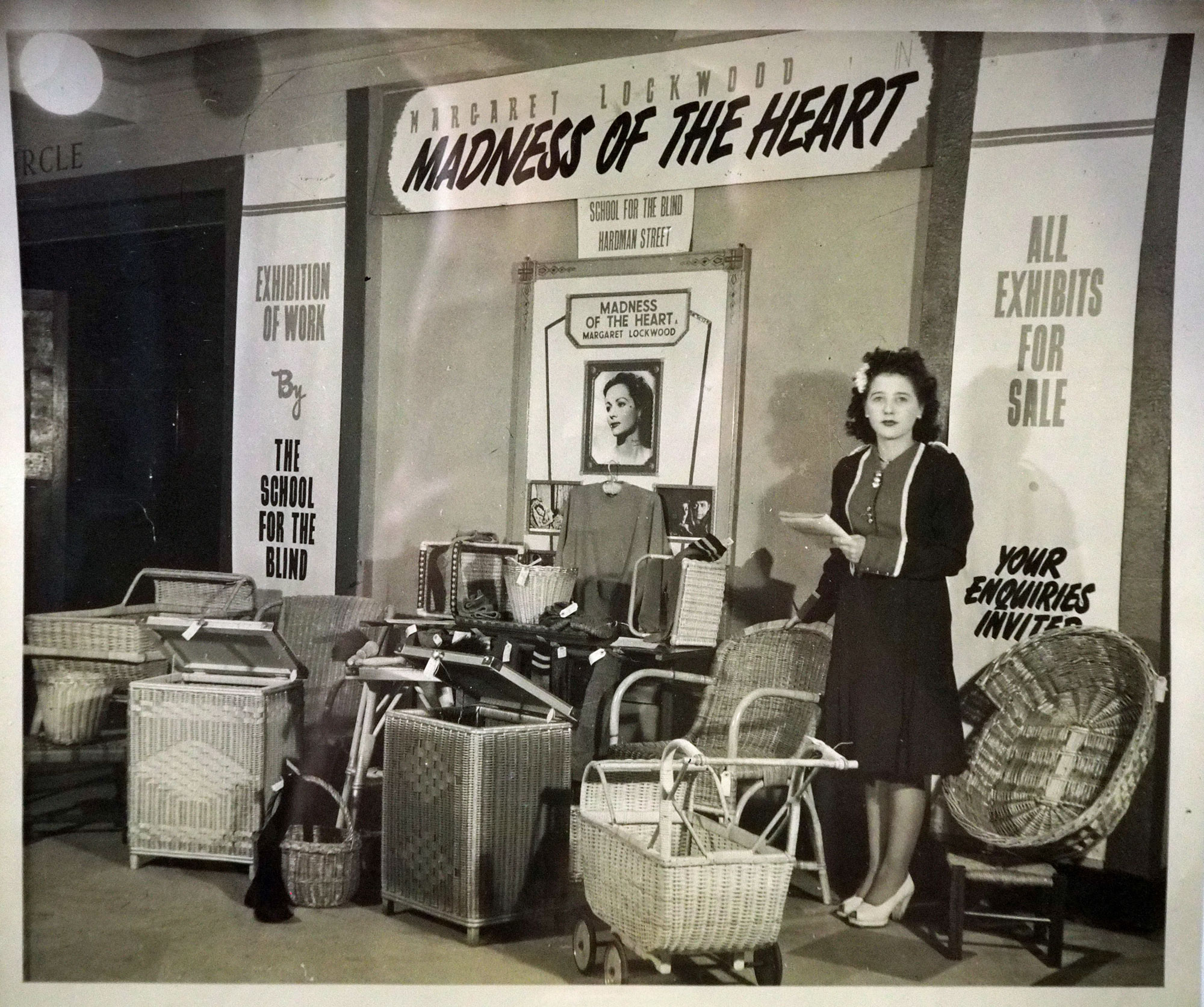

Meanwhile, also in the late 18th century, campaigning by Edward Rushton and others led to the founding of the Liverpool School for the Blind. Again it offered a way out for poor blind people who previously had few opportunities and could face bullying in the streets of Liverpool. Making baskets and brushes was so central to the trades learned at the school that these were turned into reliefs on one of the School’s later buildings.

The School also taught Braille.

Around the time of the First World War making baskets also frequently appears in the photograph albums of Guild of the Brave, a community of disabled people in Bristol. Guild members often struggled to get considered for work, and a century after the founding of the School for the Blind basket-making was still a ‘staple’ for disabled people.

On the one hand, these were very desirable craft items, which took skill to make and which not everyone could afford. At the same time, there are signs that the work cut disabled people off from a broader education and was sometimes stigmatised. Blind trade union leader Robert ‘Dixie’ Smith was among those keen to offer blind people options that did not involve baskets.

One of our researchers said her mum had shared a memory with her, that the objects made at the adult branch of the school went on display in the ‘shop’ which could be seen from the road. Her mum used to walk past dreaming of owning something; they were sought after objects and out of her price range.

Kerry Massheder-Rigby

I wish to suggest that Mr Fisher should embody in his bill a special clause which will revolutionise the conditions of the blind. Let him set up a system of technical education which will teach blind children bedding manufacture. It is an easy trade, which they can easily learn. It will give them a living wage. Then let the government earmark that trade for blind people for its own and municipal contracts. What with the needs of the Army, the Navy, and public institutions, it will employ all the blind, and even take them away from such industries as basket and brush making.

Robert 'Dixie' Smith quoted in the Liverpool Echo, 21st April 1917

John Langdon Down, who founded a home for learning disabled people at Normansfield Hospital and gave his name to Down Syndrome was exemplary for his time in extending the idea of what residents could do in as many directions as possible. Normansfield included workshops to learn trades, and an emphasis on the arts. The grounds included an ice skating rink and a theatre.

Henry Pullen was a long term resident at Earlswood Asylum where John Langdon Down was at one time the medical superintendant. Pullen made complex models including this ship and a giant carnival soldier made to amuse children in the 1870s.

Today, getting access to work and education without being limited by uninformed assumptions about ambition and capacity are still vital issues for disabled people. Institutions such as the Schools for the Blind and Deaf helped hugely develop the opportunities for a dignified life, although with not always perfect outcomes. In imagining a future, its often useful to look to what worked and what did not in the past.

References and further reading