From an article that first appeared on 27.12.16 in the Bristol Times local history supplement, free with the Bristol Post every Tuesday.

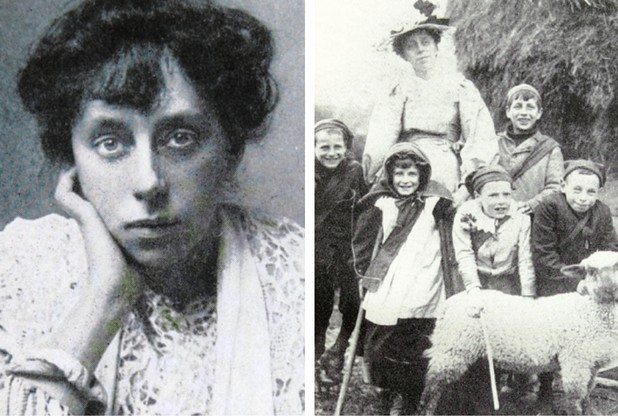

Born in Cardiff 150 years ago today, Ada Vachell grew up to be a very remarkable Bristolian, whose energy and determination succeeded in improving the lives of many of the city’s most vulnerable people. Eugene Byrne tells her story.

Armed with information from local poor relief officers, Ada Vachell spent several days in early 1896 seeking out children with disabilities in their homes. She wrote:

“Neglected ones lurked in dark corners, and at their relations’ call, crept timidly into the light. Poor, pitiful objects with paralysed or distorted limbs sat dully as they had sat, year in and year out, doing nothing and having nothing done for them.

Little children suffered in patient, pathetic fashion. The deaf lifted their impassive faces – the outcome of that silent world in which they lived. Upon the faces of the blind was written: ‘acquainted with grief’ …”

To the parents of these children, Miss Ada Vachell probably appeared no different from many of the other middle-class do-gooders who occasionally visited the poor bearing patronising strictures about the Bible and temperance.

“I dipped my head under the clothes lines, and stepped over refuse heaps that waited at the roadside to be carted away. At the end of one court a thin, sorrowful-looking girl, with a sack tied over her clothes, was scrubbing out pots and pans by a pump. She was deaf and dumb, with curious shifting eyes, behind which lurked fear.

You wondered what her life had been – how much suffering had been pressed in. ‘She’s very stubborn. Them afflicted ones often is,’ the hard-featured woman with whom she lived told me. I held out a few flowers I had in my hands, which she took eagerly.”

Yet this was to be the beginning of an organisation in which adults and children with disabilities in pre-Welfare State Bristol would find their lives immeasurably improved.

Two of Ada’s older siblings died and family legend had it that the doctor advised the distraught parents to delay the funerals as Ada was not expected to live the night either.

Ada’s Guild would give boys and girls, men and women a useful trade where they might otherwise have ended up in the workhouse. It would rescue most of them from social isolation and introduce them to new friends, many with similar problems to their own.

It would show them a world of possibilities and knowledge through talks and lectures, it would give children who had never seen a green field in their lives a holiday in the country every year.

Above all else, though, it gave them confidence and dignity, thanks to the tireless Miss Vachell – “Sister Ada” – who had a disability of her own and whose motto was: ‘Make your loss not a disablement, but an equipment.’

Early life

Ada Marian Vachell was born on December 27, 1866 in Cardiff, the daughter of William Vachell, a wealthy iron merchant who was three times mayor of Cardiff.

Her mother Marian was the daughter of Clifton businessman William Fedden, so Ada’s wider family included the brilliant Bristol aero-engine designer Sir Roy Fedden, artist Romilly Fedden and journalist and author Marguerite Fedden.

The prosperous and comfortable life of the family was shattered by an epidemic of scarlet fever.

Two of Ada’s older siblings died and family legend had it that the doctor advised the distraught parents to delay the funerals as Ada was not expected to live the night either.

She survived, but was from then on said to have a weak constitution. It also left her partly deaf. Ada later said that she had no childhood memory of Cardiff except that of going to see graves.

The family moved to Clifton in about 1875 so that Marian could be closer to family and friends.

The new home was at Severn House in Sneyd Park. Here, despite their father’s frequent bouts of what we would now call depression, Ada and her younger brother had a happy childhood, surrounded by many friends and a big extended family.

Ada was a decidedly headstrong child, and even more so as a teenager. She was said to be eccentric in her dress (“What is the good of my giving Ada a cheque for some nice new clothes? She would only spend it on others!” said her father).

She was also plainly very intelligent, though her education was patchy. She attended some lectures at the University and was said to be so good at chess that she would read a book whilst her opponent pondered their next move.

She was certainly a feminist by the standards of the time insofar as she was a strong advocate of votes for women.

She had a number of intense friendships with other girls, but does not appear to have had much interest in men, even though she could have made herself a very comfortable match – which was all that was expected of women of her class then. Perhaps she was a lesbian, or perhaps she simply wasn’t interested in getting married. To a young woman of her obvious intelligence the life of a provincial middle class wife may simply have appeared dreadfully boring and unfulfilling. She was certainly a feminist by the standards of the time insofar as she was a strong advocate of votes for women.

In other ways she was far more conventional; she was an excellent horsewoman (though she hated hunting), loved travelling, was fond of amateur dramatics, and was conventionally and devoutly Christian.

Like many women of her class she was also interested in charitable work. One of the early manifestations of this was her habit of inviting young servant girls and errand boys from around Stoke Bishop to her home on Sunday afternoons and evenings for social gatherings involving a bit of prayer and hymn-singing.

On one occasion she decided to take her girls and boys on an outing to Clevedon, hiring a horse-drawn ‘wagonette’ driven by a man who, alas, spent the day there in the pub and was completely pie-eyed when it was time to go home.

Ada sternly forbade her young charges from laughing at the poor man’s affliction (as she saw it) and patiently stood behind him all the way home keeping him awake and alerting him to forthcoming bends in the road and ditches at the side of it.

Soon she was also helping to run the Hand-in-Hand club, an organisation for Bristol factory girls, but it was a visit to London in 1895 that set her on her mission.

At the Guild of the Brave Poor Things she saw how Grace Kimmins was working with ‘cripples’ to fight the deprivation of their lives, and the sense of dependence that went with it. The Guild’s motto was ‘Laetus sorte mea’ – happy in my lot.

The Guild started out by holding meetings at Stratton Street, and these were initially just social gatherings to help adults and children with disabilities to get over the problems of boredom and isolation.

Ada, whose childhood deafness was steadily getting worse and causing her a great deal of frustration, decided she would do the same thing for Bristol. And unlike Grace Kimmins, she had at least some insight as she had a disability of her own.

The Guild of Poor Things was founded in Bristol on February 13, 1896. She had visited some of the roughest slums in town to issue her invitations to children.

The Guild started out by holding meetings at Stratton Street, and these were initially just social gatherings to help adults and children with disabilities to get over the problems of boredom and isolation.

Within weeks it had outgrown the first upstairs room and started meeting at the mission building on Broad Plain.

There were games and social activities, lectures on a huge range of subjects (which were particularly appreciated by the adult males, who usually couldn’t afford newspapers). These were soon joined by gym activities and drill on the basis that physical exercise might help many to improve their lives.

There were homemade medals bearing the Latin motto and the Guild’s emblem of the sword crossed with a crutch.

There was always a large Union Jack hanging in the meeting room and the Guild’s members were encouraged to see themselves as soldiers.

The Guild had a decidedly militaristic flavour; indeed, the London organisation had taken its inspiration from Juliana Horatio Ewing’s book The Story of a Short Life whose boy hero Leonard, who really wants to become a soldier, is disabled when hit by a carriage. Determined to overcome ‘the pain and frustration of crippledom’ he resolves to be ‘happy in his lot’.

There was always a large Union Jack hanging in the meeting room and the Guild’s members were encouraged to see themselves as soldiers who could face about manfully and bear cheerfully what inevitable hardness life holds’.

The Guild grows

Within ten years the Guild had over 200 members, and in 1906 it opened a purpose-built holiday home in Churchill, Somerset, which would remain in use into the 1970s. Here adults and children many of whom had never been more than a few streets from home would experience fresh air and countryside. The children could play freely or take rides in a farm cart, or on the donkey, which they adored.

Many Guild members, particularly the older males were, or had been, alcoholics. Some had taken up drinking because of physical pain, but others drank simply because they were bored or depressed.

Many Guild members, particularly the older males were, or had been, alcoholics. Some had taken up drinking because of physical pain, but others drank simply because they were bored or depressed. Small wonder that Ada was an ardent temperance campaigner, but also had to battle to keep her charges away from drink.

A note she wrote to a friend offers a small insight into this day-to-day work: “To-morrow I have my temperance meeting when one or two drunkards are coming whom I ought to look after. My man has promised to sign [the pledge] who had been going hard to the devil. And my legless boy is coming, and also promises to forgo drink.

I have just got him out of the workhouse and into a tailor’s shop at 15s a week. He wrote yesterday he was trying his level best and keeping straight. And I am singing Te Deums in consequence. He isn’t in the Guild – an expelled lad from a London Cripples’ Home that I have set my heart on saving.”

Designing for access

In 1913 the Guild opened its own purpose-built premises at Braggs Lane, St Jude’s, where the facilities even included a gymnasium. Designed by Frank Wills and Sons, the building is still there today. It came with a large hall; a space for lectures, events, performances and girls’ and boys’ rooms for teaching and craft apprenticeships. It was one of the first buildings in England (and possibly THE first) to have disabled access designed in from the start.

A less condescending name

By this stage, the Guild had long since been placing some of the boys (and even some girls) in apprenticeships, and paying the fees. The Guild of the Poor Things changed its name in 1917 at the request of the older boys who said it was condescending and negative, and so made it harder for them to find work; from then on it was the Guild of the Handicapped.

The name-change was in 1917, at a time when the Guild’s members were finding it much easier to get jobs. Barred from the armed forces by their disabilities, they could now take up roles which had been vacated by men who had joined up, or been conscripted.

None of this came cheaply, and the hidden part of Ada’s story is in how she succeeded in raising the large amounts of money needed for two buildings, for their maintenance and for providing facilities and services for her members.

She had a band of voluntary helpers, over whom she seems to have exerted quite stern control, to help with fundraising. She could also use all her social contacts among the great and good of the city to raise money or ask for favours.

But much of the money was raised by Guild members themselves, and even by members of their families going from door to door in some of the poorest parts of town to collect pennies and halfpennies where they could.

Ada – now known to all as ‘Sister Ada’ – was kept extremely busy. She also helped set up the Bristol Invalid Children’s School, maintained her interest in the theatre and campaigned for votes for women.

Her own childhood illness, along with a punishing work schedule (she was said to give up to 20 children a bath each day when at the holiday home at Churchill) must have taken their toll.

She died suddenly of pneumonia at her house, Foley Cottage, on Hampton Road, Redland, on December 29, 1923.

On January 2, 1924 there was a funeral service at Bristol Cathedral, though she was cremated at Golders Green the following day. Her friend Mabel Glanville, who had been living with her at Foley Cottage when she died, took over the running of the Guild.

The work of the Guild continued for many decades afterwards, though the arrival of the Welfare State in the postwar years made it less necessary than before, and it was disbanded in the 1980s.

By then it had quite considerable assets which were passed over to be administered by the trustees of Bristol Municipal Charities for giving grants to people with disabilities (see www.bristolcharities.org.uk). The Guild Heritage building is nowadays NSPCC offices.